1066 - The Battle of Hastings from the English point of view

Turbulent times in Saxon England

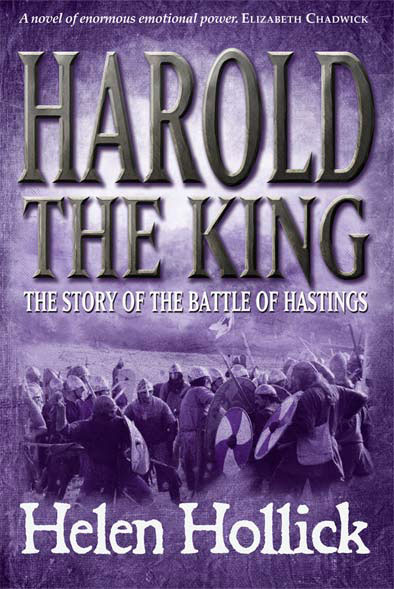

Harold the King was written because I was fed up with English history always starting at 1066. We have a rich and varied history before this date - and what we think we know about the Norman Conquest after the Battle of Hastings is mostly all Norman propaganda - to the winner the written account.

I wanted to explore the events that led to that most famous date, October 14th 1066, and that battle which changed the course of history. Who were the people, what made them do what they did, and why did they do it? That is the attraction of a novel - you can take the known facts, add in the accepted conjectures and use your imagination to fill in all the bits between.

I am proud of my novel; it is my personal tribute to the last English King, Harold II, Harold Godwineson, the man, the King, who gave his life attempting to defend his kingdom from foreign invasion by a usurper who had no right, beyond his personal ambition, to the English throne.

Harold was our legitimate, anointed King - the first English King to be crowned in Westminster Abbey, the last English King to die on the battlefield.

He died for us.

Helen Hollick's counter blast to the Norman propaganda machine, based upon the research for her novel Harold The King.

1066, the most famous date in English history. The Battle of Hastings. To be precise, the 14th of October, 1066, the day when William, Duke of Normandy, led his conquering army against King Harold II of England.

Today, more than 940 years later, one could be forgiven for thinking that Tony Blair's Labour Government had invented spin doctoring, but media manipulation is nothing new. By 1077, Duke William's half-brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, had commissioned an embroidery - now called the Bayeux Tapestry - to depict the victorious events; William of Poitiers and William of Jumièges had both written a detailed version of the Conquest. William himself had ordered the building of a splendid abbey on the battle site, the altar being placed at the spot where Harold fell. Supposedly killed by an arrow in the eye.

However, the Norman versions are heavily biased, their explicit purpose: to prove to a Papal inquiry, concerned at the level of brutality and aggression meted on the English, that William's conquest had been justified.

I smell a rat.

Within twenty years of the Conquest, after the North of England had been savagely razed and the Domesday Book compiled, King Harold II's reign of nine months and nine days was completely undermined. Despite legitimate crowning and anointing, therefore taken unto God, in the newly built Westminster Abbey, he was systematically downgraded to his pre-1066 title of Earl and discredited. William's media managers had to justify political murder.

Strip away the Norman gilding, and what do you get? Twisted truths and blatant lies. Start with the fact that William had no right whatsoever to claim the English throne.

He was the result of Duke Robert's liaison with Herleve, the daughter of a tanner. No-one in Normandy expected Robert to die before he took a wife and had a legitimate heir. In fairness to the boy, who grew up to be little more than a sadistic, psychopathic tyrant (well I am a Harold supporter) he did suffer a traumatic childhood. The Norman nobles were not happy bunnies, they did not want an eight year old by-blow as their next Duke. As a child, William had to flee for his life more than once; saw his trusted servant murdered before his eyes. What a pity there was not a Norman equivalent of child counseling. Had there been, perhaps England would have been left in peace, and William would have kept his land and wealth-grubbing hands off.

William's claim, in 1066, was that his great-aunt, Emma, had been Queen of England - the only woman to have been queen to two different kings. Æthelred, better known as the Unready, and Cnut - that's the p..c. spelling of Canute - the King famous for attempting to holding back the tide. Her firstborn son was Edward, later canonised and called the Confessor. Blame the Conquest on him. He was sent into exile when, with Æthelred dead and England falling to the conquest of the Dane, Cnut, Emma decided to remain queen by marrying again. For more than thirty years Edward languished in Normandy. He was in his early teens when he left, a man approaching middle years when he came back, recalled to be crowned King of England. He was a man indoctrinated with the Norman way of life, and probably, would have preferred to take Holy Orders. He may have declared a vow of chastity, or he may have been gay. There are indications to infer he was. Prime among them, his wife, Edith, bore him no children. In this period of history barrenness was always the woman's fault. Edith was never blamed. Edward even took her back as wife after a nasty incident when her father was accused of turning traitor and forced into exile. Edith was sent to a nunnery, always a woman's fate, but after a year, with Godwine forgiven and re-instated as Earl, she too was recalled.

Oh, and by the way, the Normans were not French, although William's great-grandfather had embraced Christianity and the French, civilised, way of life. The Normans were re-located North Men. They were Vikings.

According to William's "biographers", King Edward had appointed him his heir, and despite swearing an oath to support his claim, Harold had seized the throne and in indecent haste, and had himself crowned on the same day as the old king's funeral, January 6th 1066. Outraged, William immediately ordered an invasion of England, and while Halley's Comet blazed in the sky, a fleet was assembled. In September, he crossed the English Channel without mishap. In the meantime, Harold's brother, Tostig, possibly supporting William, had invaded Yorkshire. Moving swiftly, Harold marched to Stamford Bridge near York and won a victory, but when he heard of William's landing, he had to return, hot foot, south.

Medieval spin doctors would have us believe that Harold was a poor commander who fought with a tired and depleted army against the elite supremacy of Norman cavalry. Victorious, William marched on London and on Christmas Day was the first king to be crowned in all splendour in Westminster Abbey. Personally, I think his title of bastard is for the other use of the word, and has nothing to do with his lack of legitimacy.

So how had Harold become King? His father, Godwine, was the most powerful man beneath Edward. He had risen to power under Emma and Cnut. Five of his six sons became earls and his daughter, Edith was Edward's childless queen. When Godwine died Harold stepped into his shoes as Earl of Wessex. Harold proved, several times, that he was an able and capable soldier. He conquered Wales, not Edward I in the thirteenth century. Harold became King of England because he was the most suitable man for the job. Edward could not have appointed William as heir, things did not work like that in Anglo-Saxon England. When a successor had to be found, the most suitable man was chosen by the Council, the Witan. William might have been considered, but against Harold? No contest.

The coronation took place on the day of the funeral because, knowing the king was dying, everyone of importance had been summoned to the Christmas Court. By early January they needed to return home, and England could not be left vulnerable until the next calling of Council at Easter. There was nothing untoward about accomplishing such important issues on the same day.

But what of the claim that Harold had pledged an oath to aid William? In 1064 Harold went to Normandy, his voyage duly recorded on the Bayeux Tapestry. Norman sources declare he went to offer William the crown; more likely he was hoping to achieve the release of his brother Wulfnoth and nephew Hakon, held hostage by William since that temporary disgrace of Earl Godwine back in 1052. (I'll not go into detail, suffice to say the exile was caused by some Normans stirring trouble in Dover. Godwine refused to take their side, hence his falling out with the King. For some reason, when the Normans went home they took the two boys with them.) Harold did return to England with Hakon, but Wulfnoth never saw his freedom again.

While William's guest, Harold went on campaign with the Duke, earning himself honours by rescuing two men from drowning near Mont St. Michel (again depicted in the tapestry). Riding with William, Harold would have discovered what sort of man he was. Dedicated to his cause. Single-minded. Ruthless. At the siege of Alencon, William had men skinned alive for daring to taunt him about the nature of his mother's background. William was the one who invented death by incarceration in a dungeon. He was quite capable of slaughtering innocent women and children.

At William's Court, Harold was forced to swear, on holy relics, an oath to agree to support the Duke's claim to the English throne. Did he have any choice? What would have been the consequences for Harold and his men if he had refused? William, as his own vassals knew and Harold had discovered, was not a man you said non to. If you knew you would be locked away for the rest of your life and your men butchered, wouldn't you have risked perjury?

For a Saxon nobleman it was a matter of honour to protect those you command. To place his men in danger by refusing, Harold would have brought a greater dishonour on himself. Only the Norman spin doctors claimed an oath made under circumstances of coercion was binding.

As for Harold's command at Hastings - he showed aptitude and courage, dignity and ability. Norman propaganda states that he fought with tired men, with only half the fyrd - the army - and without the support of the North. Tosh!

In mid-September, Harold had marched from London to York in five days to confront his jealous, traitorous brother, Tostig, who had allied with Harald Hardrada of Norway. The southern fyrd, on alert all summer, had been stood down. He took only his housecarls - his permanent army - north, gathering the men of the midlands to him as he marched. Undoubtedly, the housecarls were mounted for no infantry could cover that distance so quickly. Already the fyrds of the north had fought and lost a great battle at Gate Fulford, outside York. Under Harold, they fought again - this time to win - at Stamford Bridge.

It was not that the nobility and the men of the fyrd did not want to support Harold at Hastings; they could not, for their numbers were savagely depleted, many of the survivors wounded and exhausted after fighting two battles. It would have been impossible for them to have marched south when news came that William had landed. The northern earls did in fact follow Harold as soon as they could but, of course, by then it was too late.

The battle that took place seven miles inland from Hastings is almost unique for this period. Fighting was usually over within the hour, two at most. This battle lasted all day. The English, for the most part, stood firm along the ridge that straddled the road out into the Weald, stood shield locked against shield, William's men toiling again and again up that hill. This was deliberate strategy on Harold's part. He and his men had marched to York and back, fought a battle in between. Doesn't it make good sense to make the opponent do all the hard work? Yes, perhaps Harold would rather have waited before committing his men to fight, but he had no choice in the decision: once out into the Weald it would have been difficult to stop William. Within the Hastings peninsula, he and the extensive, deliberate, damage he was doing to people and property were firmly contained. Harold had to keep him there, therefore Harold had to fight.

He stood his men, firm, along the ridge, forming the shield wall. Side by side (to coin an over-used Blairite phrase, "shoulder to shoulder") Shouting their contempt, clashing spear and axe against their shields, hurling abuse down that steep, grass hill that so rapidly became a morass of mud and blood:

"Ut! Ut! Ut! - Out! Out! Out!"

Three times William was unhorsed. Three times the Normans retreated; only the fear of William's wrath held them together, although the Norman writers naturally portrayed their blind panic as strategic withdrawal. Only once did Harold's men let him down. The right flank broke - assuming William's men were beaten they tore down the hill after them, Being cavalry, the Normans were able to re-group. The result was outright slaughter, every Saxon was killed.

Nor was William's crossing of the Channel as straightforward as his spin-doctors suggested. He had sailed earlier in the summer, but was turned back. Bodies and wreckage on the Normandy beaches were buried in secret. Why? If bad weather was the cause, why the need for a media black-out? A mass cover-up? It is more likely that he met and was repelled by the superiority of the English Navy, a disaster that subsequent propaganda would most definitely suppress.

And so to Harold's death. The Bayeux Tapestry depicts a man wounded by an arrow in his eye, and another being felled by a sword, the words 'Here Harold is killed' above both. Which one is Harold? Well, it is not the one with the arrow. Arrows travel in a trajectory. They go up, form an arc, come down. Can you honestly believe that there stood Harold, an experienced soldier, looking upward as arrows came over?

King Harold II of England died at the hands of four of William's ignoble noblemen. They dismembered and decapitated him.

The truth of Hastings? Our last English king died slowly and bloodily. He was savagely murdered, hacked to pieces on the battlefield that later became known as Hastings. Ðot wos göd cyning. Harold was a good king. He gave his life defending England from foreign invasion, and has paid the penalty of deliberately twisted truth ever since.

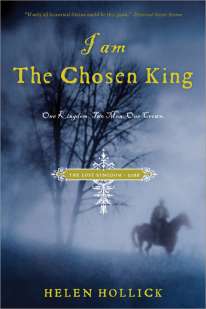

The year is 1002, Emma of Normandy is to marry King Æthelred of England. It is a marriage that is as doomed to fail as Æthelred's entire reign. But Emma is to find her own happiness when Cnut seizes the English throne…

Not only is Æthelred a failure of a king, but his young bride Emma of Normandy soon discovers he is even worse as a husband. When the Danish Vikings led by Swein Forkbeard and his son Cnut cause a maelstrom of chaos Emma, as Queen, must take control if the Kingdom - and her crown - are to be salvaged. Smarter than history remembers, and stronger than the foreign invaders who threaten England's shores, Emma risks everything on a gamble that could either fulfil her ambitions or destroy her completely.

"Emma, the Queen of Saxon England comes to life through the exquisite writing of Helen Hollick who shows in this epic historical tale how one of the most compelling and vivid heroines in English history stood tall through a turbulent fifty-year reign of proud determination, tragic despair and triumph over treachery."

A section of this article was my Thesis, presented towards gaining a University of London Diploma in Medieval History, 2000-2001.

Introduction

Before the Conquest of England by Duke William of Normandy in 1066, the narrative of events and the passing of history was written down, not in one, but several records. Not only in England, but also in Scandinavia and Normandy. After the Conquest new parts were added, and some of the original subtly re-written to better accommodate the new rule of the Normans.

Stripped of conjecture, propaganda and imaginative interjection the subsequent accounted life of Queen Emma is sparse on detail, little more than a framework of basic recorded fact. Yet her curriculum vitæ is a rainbow of colour as intricate and almost as controversial as that of the later, more famous queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Wife and queen to both Æthelred II and Cnut; mother of the kings Harthacnut and Edward (the Confessor), Emma was to become involved in political intrigue, flee into exile at least twice, be implicated with the vicious murder of one son, and accused of treason by another who forcibly deprived her of all her wealth and property.

The English narratives written in those years before 1066, and preserved in the collection now known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, were contemporary with Emma's own life. They comprise a variety of documentations, written at various times and places by men of the Church. The surviving documents are mostly later copies and compilations, their origin difficult to identify. Emma is mentioned but not Æthelred's previous wife - very few women are included in the Chronicle. In it, and other documentations, she is referred to by the English name she was given on her marriage, Ælfgifu. Emma, however, was her Norman name by which she is most commonly referred to in English historiography.

Some Norman narratives were unflattering of Emma's initial appearance in their writings. An anonymous Latin poem, Semiramis,(1) is a satirical drama of the early eleventh century, presenting a whore/queen who agrees to a marriage with an adulterous horned bull, who later transpires to be Jupiter. Semiramis is probably Emma, and Jupiter, Cnut. The unknown author used the work to criticize Emma's male relatives, portraying their weaknesses through her will of independence.

1) Also see below Page 09

Page 1

William of Jumièges provided the base of the "official" Norman story-line assembled in the 1050's, while William of Poitiers added to its length and legal shaping after 1066. The Norman-born Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert of Jumièges fled from England in 1052, returning to Jumièges where he lived until 1055. His feelings towards England must have consisted of a mixture of emotions. From him, William perhaps received a very personal and biased account as to the events of English history. After the Conquest, all stories of pre-1066 were by necessity over-shadowed by the outcome of Hastings, Emma remaining as a link through the politics of her family connections, marriage and motherhood.

In Scandinavian writings, she serves to place Harthacnut as King, and to explain the choice of Edward as King instead of Cnut's sister's son, Swein Estrithson.

While in exile in Bruges, during the brief reign of Harold I (Harold Harefoot) Emma commissioned the Encomium Emmæ Reginæ - the Encomium of Queen Emma. Ostensibly, it is a eulogy of her second husband, the Danish King, Cnut, but it is also a work that would be admired by any modern-day politician for its remarkably subtle bending of the truth - an early medieval equivalent of spindoctored media manipulation. Among other blatant inaccuracies, the work totally conceals the fact of her fourteen year marriage to King Æthelred II !

Conjecture and interpretation surrounds any analogy of this remarkable woman, but was her existence and position in England that of a pawn, used as a bargaining power for the making of treaties and the gaining of crowns? Or was she a queen in her own right, commanding the political power to rule as regent during Cnut's absences to his Scandinavian kingdoms across the sea, and the ability to ensure the son of her choosing should succeed to the throne?

Page 2

Æthelred

When Æthelred (the Unready) took Emma of Normandy as his wife in 1002, he was the first English king since 855 to take a foreign bride. Presumably, his intention was to elicit the aid of Duke Richard II of Normandy against Scandinavian raiders who had been using his Norman ports as a base to attack the English coast. The strategy did not work, for by 1013, invasion by Swein Forkbeard, King of Denmark and his son Cnut precipitated Emma, her two sons and later Æthelred himself, to flee to Normandy into exile. After Swein's unexpected death, Æthelred returned to England but he was to die in 1016, leaving the way open for Cnut to invade and, ultimately, conquer. It is often forgotten that Cnut was a foreigner who invaded, conquered and subsequently took control of the English Kingdom. There is no 21st Century hostility towards his Danish rule, yet many supporters of Harold Godwineson, King Harold II, condemn the invasion, conquest, rule and domination by Duke William of Normandy fifty years later. Perhaps this is because Cnut wished to be seen to rule with fair judgment, made no attempt to implant Danish ways over an English populace, and except in a few cases, retained the English lords, English laws and English ways. Cnut became 'more English than the English'. Duke William imposed a harsh, resented rule.

Emma was the youngest daughter of Richard I Duke of Normandy, one of at least nine children, daughter almost certainly to the Danish-born Gunnor, and therefore sister to Richard II who became duke in 996, and Robert, Archbishop of Rouen. She was to become aunt to Duke Richard III, his son Duke Robert, and great aunt to Duke William of Normandy, known after 1066 as the Conqueror. She came to England betrothed in marriage to Æthelred as his second, or possibly third, wife. The date of her birth is unknown, the latest date being c 990, assuming that she was unlikely to have been younger than twelve years of age when she crossed into England as queen. At most, she was in her early twenties - the usual age of marriage, however, for daughters of the noble-born was between 13 - 15.

Although she could speak Danish, her mother's native-born language, on her arrival in England she could speak no English. Teaching her would probably have been among the first priorities, the task no doubt falling to the higher-born ladies of the Court, as both mother-in-law and sister-in-law were no longer alive.

Æthelred had come to the throne with a corrupt suspicion of involvement in his brother's murder hanging over his shoulders. On 18th March 979, the then King, Edward, was murdered at Corfe Castle, Dorset, in a way that shocked even the hardened men of that time.(2) Reputedly, the murder was instigated by Edward's step-mother, Æthelred's mother Ælfthryth, while a guest of her household. Whether this is so, or the murder was committed by Æthelred's retainers is uncertain. Edward was unpopular and inclined to a violence of temper and deed. England was still reeling from the sudden death of their father, Edgar, in 975, and may have been on the brink of the upheaval of semi-civil war. There is no conclusive evidence that either Ælfthryth or Æthelred were implicated, but no-one was punished or held responsible, and Æthelred, crowned king a month later, began his reign under a suspicious atmosphere. Thirty years later the death of his half-brother, by then called Edward 'the Martyr', was still actively remembered.(3)

2) F.Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England p.374 notes. The murder was committed under circumstances considered to be an act of gross treason and betrayal. (c. Life of St Oswald.) Æthelred's retainers met the young king's arrival with honourable respect but as he rode into the courtyard and before he could dismount, surrounded him and stabbed him to death.

3) F.Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England p.374 notes. There is a reference to Edward's death in a charter of 1001 (Laws of Æthelred v 16) granting land to the nuns of Shaftsbury.

Page 3

Throughout his reign Æthelred was to prove a weak king. Æthelred "un ræd" - later wrongly corrupted to "unready" and literally meaning "ill-counseled" a play on the meaning of Æthelred - "noble counsel." He was indecisive, inclined to rages of temper and sporadic violence, and proved ineffective in war, as Stenton remarks, "which is very remarkable in a king of his line."(4)

Within two years of his succession Scandinavian raiders were accosting England, drawn no doubt, by the weakened defenses and confusion of government. The early raiders, from 980 to 988 came in small groups, marauding the coastline as pirates. A significance of these raids was that for the first time England was ushered into diplomatic contact with Normandy.

Duke Richard I was the grandson of the founder of Normandy, but it was no longer viable for Scandinavians to make new settlements in the Duchy. Conscious of their origins however, Norman nobility remained friendly with their own kind, and Norman ports became safe havens for "Vikings" returning from raids on England. By 990 open hostility existed between the English and Norman courts and word of the increasing enmity reached Rome by the autumn of that year. In consequence, Pope John XV dispatched an envoy to England, with the express command of arranging an agreeable treaty between the two countries. Æthelred and his council, welcoming the envoy, prepared a set of terms that made provision for an acceptable, peaceful, reparation of all injuries that either side might suffer from the other, and that neither country would entertain or condone the others' enemies.

Two of Æthelred's thegns and the Bishop of Sherborne accompanied the Pope's envoy into Normandy, and at Rouen in the early spring of 991 the Duke agreed terms. Five months later, raiders, larger than any previous force, again appeared along the English coast - one of the raids being at Maldon, Essex, the tragic outcome and death of the Saxon thegn, Byrhtnoth, being immortalised in epic poetry.(5) The widespread destruction forced the English government to raise a heavy tax in order to buy an agreement of peace, thus setting a precedent that was to be exploited by the raiders to its fullest potential during the next twenty five years.

By 997 the form of pirate raiding had altered to resemble that of an invading army prepared to systematically raid and plunder, attacking Wessex, Dorset, Hampshire and Sussex in 998, and the following year, Kent. After the summer of 1000, the Vikings over-wintered in Normandy - the treaty that had been previously made between the two countries being obviously discarded. Although a raid on Exeter was successfully defended, the North Men were proving to be masters of the English Channel, the situation only being relieved in 1002 by a tribute payment of £24,000. Within a week of making the payment, Emma was to be married to Æthelred.

4) F.Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England p.374

5) S.Pollington: The Warrior's Way pp.32-36 The poem usually called the Battle of Maldon first occurred in the Cotton Collection but was destroyed by fire in 1731 (in which the manuscript of Beowulf was also singed) although most of the work survived in a transcription by a copyist named Elphnstone. Although some detail may have been misinterpreted, and some is plainly missing, the basic facts appear reasonably accurate. Byrthnoth's death occurs in a number of references: the AS Chronicle. two obituaries one from an Ely Calendar of the late 12th c the other from a Winchester calendar from the early 11th c. and also in the Life of St Oswald and the Book of Ely.

Page 4

Emma's first appearance in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle(6) was not to record Æthelred's marriage, but as an announcement of her arrival in England. She was referred to as "Lady" (HlÆfdige)(7) and re-christened with an English name, Ælfgifu. The consequential political connection with Duke Richard and Normandy only becoming significant to a writer recording events with the knowledge of hind-sight.

As Pauline Stafford points out, "In 1002 and 1013 she [Emma] was identified as 'Richard's daughter' not primarily as 'Æthelred's wife'."(8) but her Norman birth was to prove particularly significant when her heir-less son, Edward, was reaching old age. The right of inheritance to the English throne through his great-aunt was one of the claims made by Duke William.

Whether the marriage led to another treaty, or an amicable understanding between Æthelred and Duke Richard is unknown. Outright conquest by the Danes was not on the agenda in 1002, and the English government, although financially in difficulties and badly shaken, was still intact. A political crime of Æthelred's own undoing in the autumn of 1002, however, brought the collapse of England closer.

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: "That year [1002] the king commanded killed all the Danishmen in England on St Bricius' Day [13th November] because the king was informed that they meant to beguile him out of his life .... and so have his kingdom afterwards."(9)

It is unlikely that such an order could have been obeyed throughout a third of England, for places such as York and Lincoln, for instance, were Danish towns, but a massacre of the Danes did occur and was remembered long afterwards. "In a charter to St Frideswide's minster Æthelred himself refers to the slaughter of the Danes in Oxford."(10)

Queen Emma is again mentioned in the Chronicle for 1003, when Swein of Denmark's raiding penetrated further inland than usual. His excuse - if he needed one - was as a retaliation for the death of his sister in the St Brice's day massacre. Exeter, held by Emma as Dower land, was betrayed to the invaders thus making open access into Wessex.(11) Her reeve, a Frenchman named Hugh, was directly blamed.

Exeter was already established as a town connected with the queen of England, and its attack may have been as a deliberate antagonism against a marriage which had been designed to facilitate the ending of the Danish using Norman ports.

Raiding penetrated almost sixty miles inland towards Reading, and tribute to buy peace in 1007 reached £36,000.

In 1004/5 Emma gave birth to her first son, Edward. The new young queen had performed her duty and produced an heir.

6) A.Savage (trans): Anglo-Saxon Chronicle p.148 "That same spring the Lady Ymma Aelfgifu Richard's daughter came into this land."

7) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith pp.56-57

8) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith p.7

9) A.Savage (trans): Anglo-Saxon Chronicle p.148

10) F.Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England p.380

11) A.Savage (trans): Anglo-Saxon Chronicle p.148 "Exeter was ruined because of the Frankish peasant Hugh whom the lady had set up as her reeve."

Page 5

There are no records of the patronages that she was to so generously give during her later time as wife to Cnut, her appearances in the witness lists come in small clusters, probably in connection first with her actual marriage, and then with the births of her children.

Creating a new fleet of warships, the English government was anticipating meeting Swein off the Kent coast at Sandwich in the summer of 1009. Before the Danes arrived one of Æthelred's commanding thegn's, Wulfnoth, was accused of treason and subsequently took twenty ships with him on his own course of pirating along the south coast.(12) His accuser followed with a further eighty ships which were driven ashore by a storm, and destroyed by Wulfnoth.(13) This was, undoubtedly, the same Wulfnoth who was the father of Godwine, Earl of Wessex, in turn, the father of King Harold and Edith, wife to King Edward, Emma's son.

With his fleet weakened by one hundred ships, the King withdrew from possible confrontation and returned to the security of Sandwich harbour. On August 1st Swein occupied the Sandwich anchorage, and, to secure their own safety, Canterbury and eastern Kent bought him off.

By 1011 Canterbury was again under attack, but peace was not bought until a year later with ££48,000. Archbishop Ælfheah had been captured in the raiding, and not permitting any ransom to be paid for his release, was barbarically killed at Greenwich.(14)

Resilience to the repeated warfare was high among the English, but the collapse of defense was beginning to take effect on morale. The King's indecisiveness and government inability to organise a concerted effort of action created an ideal opportunity for an acceleration of Danish ambition. The expedition of 1013 was, from the first, intent on making Swein, King of Denmark, King of England also.

His hope that northern England would welcome him and offer a base for attack was not misjudged, he was accepted as king by Northumbria, Lindsey and all the Danish settled lands south of the Welland and east of Watling Street.

Oxford and Winchester soon fell to him, followed by Mercia and the central shires of Wessex. He then turned on London and Æthelred himself. After the initial attack failed he retreated to complete his submission of Wessex and soon after London capitulated, depriving Æthelred of his final stronghold.

Emma and her children had already been sent into safety in Normandy. Æthelred was forced to follow her into exile, leaving Swein of Denmark in command of England. Whether he went as a strategic withdrawal or as an abdication is not mentioned.

12) F.Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England p.382

13) M.K.Lawson: Cnut p.47

14) F.Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England p.383 The Danes were raiding in Kent during the last weeks of September 1011. Probably because Kent was drained of financial resources it was not until April 1002 that the price for their departure was paid. The ransom for Ælfheah was a separate demand. Unexpectedly, Swein died a few weeks later on 3rd February 1014. His fleet in the Trent gave immediate allegiance to his son Cnut who was then no more than a youth. The leading Englishmen sent an envoy to Normandy to offer terms for Æthelred's return, terms that demanded his promise to rule more justly than before - the first recorded agreement made between a reigning king and his subjects, preceding the more famous Magna Carta by several hundred years.

Page 6

Unexpectedly, Swein died a few weeks later on 3rd February 1014. His fleet in the Trent gave immediate allegiance to his son Cnut who was then no more than a youth. The leading Englishmen sent an envoy to Normandy to offer terms for Æthelred's return, terms that demanded his promise to rule more justly than before - the first recorded agreement made between a reigning king and his subjects, preceding the more famous Magna Carta by several hundred years.

Commanding an expedition against the Danes in Lindsey in April 1014, Æthelred met with no fighting, for Cnut, with little experience of command, withdrew to Denmark - but not before landing at Sandwich to set ashore the hostages given to his father by the men of northern England.(15) Each of the hostages was released after terrible mutilation, Cnut therefore abandoning the Danish men of Lindsey to a military execution, ruthlessly ordered in retaliation by Æthelred.

Cnut's complete disregard of his Danish allies was seen as treachery, even in southern England.(16) There is no doubt that northern England temporarily regarded both Cnut and Æthelred with equal hostility, which explains why, within a few months, the north proposed a son, Edmund (Ironside), by Æthelred's previous wife as king.

Æthelred was in a weak position, England was left exposed to attack. With an army raised through his brother's help, Cnut returned and was preparing to march on London. Mending their differences in the face of mutual need, Edmund had come to give aid to his father, who may have already been fatally ill, for on April 23rd 1016 Æthelred died.

The situation was abruptly changed and the magnates in London immediately elected Edmund as King of England; Cnut's prospects of achievement appeared bleak, but within a few days Eadric Streona of Mercia and the noblemen of Wessex met at Southampton to swear fealty to the Dane. The crown of England was once again open to dispute and put up as a prize for the strongest man to win.

Emma remained in London, which was to be besieged by Cnut's army twice. Cnut followed Edmund westward where a series of indecisive battles were fought. Altering to the offensive, Edmund's forces relieved London and drove Cnut onto the Isle of Sheppey where the noblemen of England again changed allegiance.

Wessex was now ranged behind Edmund, although some sources imply that Eadric Streona was to yet again double-cross the acclaimed king.(17) The two armies were to meet at Ashingdon - an unlocated place, either in Kent or Essex - on the 18th October 1016. Edmund had mustered together a large force, but during the course of battle, Eadric retreated from the field, leaving Edmund to fight on alone. The majority of his troops were killed, though Edmund himself managed to retreat.

A few weeks later, at Deerhurst on the Severn, agreement was made between Cnut and Edmund to divide the Kingdom, Edmund having Wessex, Cnut the north.

London, caught in the middle between the two, was left to buy its own peace.

15) F.Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England p.386 & M.K. Lawson: Cnut p.19

16) F.Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England p.387 The Abingdon Chronicle remarks uncompromisingly that the poor of Lindsey were betrayed by Cnut

17) M.K.Lawson: Cnut pp.38-39 Much is known about Eadric Streona - The Acquisitor - nicknamed by the 11th c Worcester monk Hemming. The chronicle in 1009 ".... but it was hindered by ealdorman Eadric as it always was".

A.Savage (trans): Anglo-Saxon Chronicle p.151 implies Eadric's treachery but this could have been added in hindsight after Eadric Streona's betrayal of Cnut and subsequent execution.

Page 7

Cnut, The Danish Conqueror

Edmund's leadership qualities were to prove more than capable of rallying the English to fight, the military capability at his command was almost certainly far superior to that which Cnut could call upon and the invaders had come under considerable pressure. "[Cnut] was nothing more than a Viking warlord facing the prospect of imminent defeat at the hands of superior forces closing in upon him under resolute leadership."(18)

The agreement to divide the kingdom was not, as events turned out, because of defeat at Ashingdon, but because Edmund was incapacitated, in all likelihood badly wounded. A wound that was to prove mortal, for a few weeks later, he died, leaving Cnut as undisputed king.

With her two sons by Æthelred, Edward and Alfred, remaining in safety in Normandy - Edward was to live there in exile until 1041 - Emma was to be taken in marriage by Cnut, the conqueror of her first husband's kingdom. By him, she had another son, Harthacnut and a second daughter Gunnhilda.

Most references to her in charters and similar documents occur during this period, when she was Cnut's queen.(19) Her own narrative, the Encomium Emmæ Reginæ, as mentioned on Page 1 above, was commissioned as a eulogy for her Danish husband.

It is somewhat ironic, perhaps, that Emma's first marriage to Æthelred was contracted in the hopes of stopping Viking raiders from using Norman ports from which to attack England, while her second was to one of those self-same raiders who not only ravaged, but conquered the kingdom. "Emma was perhaps luckier than many of her lowlier predecessors" says Jesch, "who were forced into marriage with a Viking leader. Cnut, once he was King of England, became more English than the English themselves and a model Christian husband."(20)

Cnut already had a wife, Ælfgifu of Northampton, the daughter of ealdorman Alfhelm, his marriage to her most probably undertaken to secure support in the north of England.(21) For such an alliance to be effective she must have been an acknowledged consort rather than a mere mistress. Cnut's father's expedition in 1013 was solely intent on making Swein King of England, he knew already that he would be welcomed - because he had already contracted an alliance through the marriage of his son? Cnut was, then, only young but certainly old enough to be fighting alongside his father, therefore of an age to take an Anglo-Saxon wife. By 1016 when the northern nobility declared him king, Ælfgifu could have already given Cnut his two sons, Swegn and Harold. A comparison can be made with the later unrolling of events involving Harold Godwineson (Harold II). He had a contracted marriage of very many years with Edith Swannhæls (the Fair) who bore him at least six children, yet either just before or after his election as king in 1066 he set her aside for a formal church vowed marriage.

18) N.J.Higham: Death of Anglo-Saxon England p.76

19) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith pp.231-232 Emma's appearance on the witness lists, together with her titles, set her apart among the earlier English queens. Between 1018-19 her signature appears between or after those of the archbishops; after 1019 she appears after the King. While appearing jointly in the Winchester charters of 1033 "I Cnut of the English with my queen Aelfgifu." Regina, queen, is her most common title during Cnut's reign.

20) J.Jesch: Women in the Viking Age p.100

21) M.K.Lawson: Cnut p.47

Page 8

Anglo-Saxon marriage laws were a complexity to the later Christian established Norman writers. The marriages - for Cnut, Harold II and possibly Æthelred - were perfectly legal, the modern equivalent of a common law or register office marriage as opposed to a full church wedding. The difference being that the more important marriage was diplomatically and politically sealed by the blessing of the Church and therefore inseparable, whereas a common law wife could be simply and easily divorced.

Harold II did not, in fact, set aside Edith, nor did Cnut do so with Ælfgifu, although she was probably expected to remain within the precincts of a northern estate. In 1023 one of Ælfgifu's sons was offered as hostage,(22) which implies that Cnut acknowledged and recognised the boy as his own, and Ælfgifu remained of sufficient importance to later be appointed as regent of Norway on behalf of their eldest son Swegn.(23)

Cnut, however, required the dignity and importance of respectability. "Emma was the legitimate, consecrated queen, Cnut on the other hand, had a well-earned reputation as a 'prince of pagans', he badly needed a new image as a Christian King fit to take his place among the crowned heads of Europe."(24)

She was not only an English queen. Her father was Norman and her mother was Danish, making Emma Norman/Danish by birth and English by marriage, the three collectively useful for Cnut's purpose.

Undoubtedly there would have been negotiations before the marriage could take place, either between Emma herself or her Norman relatives. Emma, in the Encomium, takes all the credit for the arrangements. Whether in 1016/ 1017 she was in Normandy or had remained in England is also unclear. It is possible that she was trapped in London during Cnut's attacks - even that she was captured. If she did leave it would not have been until after Edmund's death on 30th November, and perhaps even then, she may have retired into her own held Dower lands - the walled town of Exeter for example.

As widow of the king these were still her lands, she would have been reluctant to give them up too early in proceedings. Under Edmund her respect and dignity as the widow of the king's father would have been assured, and until a conclusive outcome, there was no necessity for her to flee abroad. Leaving England would have left the security of her future vulnerable, and would have meant losing everything. In all accounts, however, she is linked with London and the city's heroic resistance. Whether through political negotiation or because she was pushed into an inescapable corner, Emma was unable to resist Cnut's summons that she be brought to him as wife.

Their marriage took place in the mid-year of 1017, but the writer of the Chronicle that recorded it saw the ceremony as a culmination of events and not as a strict chronology. Emma had become wife to a conqueror, all the hostilities of previous years therefore ceasing by the taking of England's most important woman in marriage. For a retrospective writer Emma was now, in addition to being a link between England and Normandy, a link with England's past. She was queen/cwen, a widow of a dead king and a living wife to a conquering new one.

22) M.K.Lawson: Cnut pp.94-131 Thorkell the Tall in 1023 seems willing to have accepted one of these sons as hostage in exchange for one of his own.

23) See below Page 12

24) H.Leyser: Medieval Women p.79

Page 9

Her marriage was to attract criticism in Normandy, for example in the satire Semiramis, written in the early 11th Century.(25) As the more official versions began to emerge, these critical views became lost, either voluntarily or by deliberate cause.

William of Jumièges and William of Poitiers' written accounts were politically biased towards Norman glorification, the English players almost forming merely "bit parts" in the rapidly unfurling drama of Norman history. Emma herself only featured because of the hierarchical family connections she brought to Duke William - marriage to two kings, mother of two more, and mother-in-law to the splendid marriage of her daughter Gunnhild to Henry, King of the Romans, the future Emperor. Any previous doubts about her marriage to Cnut were drowned by this prestigious genealogy. The Norman line of succession was raised to its full height by her and her children, and Normandy itself reached a glorified status by offering her and Edward a place of sanctuary during the troubled years of exile.

The German, Thietmar of Merseburg, heard of events in England soon after Cnut's conquest, the Queen's predicament well suited his condemnation of the Danish King Swein, and his sons' misdeeds. His Emma is a portrayal of a widowed queen worn down from the perils of attack, seeking only peace and being offered a choice of marriage or exile, along with threats of murder for her companions and sons.

Because of the resounding implications of conquest by Duke William of Normandy, Scandinavian political rule and influence did not survive in England after 1066, but during the first half of the eleventh century inter-action between the two kingdoms was of prime importance. For the Scandinavian writings, the Lady of London could only add to the heroic element of traditional saga. Emma was a widow, who, in later tales, made an attempt to escape London and Cnut's siege, appearing as a weak female, abandoned to her fate, a prize to be won in the glory of victory.

Anointed and crowned as King, the only remaining danger to threaten Cnut's interests came from Normandy where Æthelred's two surviving sons, Edward and Alfred were exiled.

For the first half of his reign he was to be protected against any attempt to restore the royal line of Wessex by the goodwill of the Norman court, secured by marriage to the Duke's sister, "but Richard II, his ally, died in 1026 and Robert the Duke's younger son who inherited the duchy in 1027 from a colourless elder brother, was an adventurous youth unlikely to be bound by any understandings to which he had not been a party."(26)

25) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith p.12

26) F.Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England p.408

Page 10

In an attempt to make good the alliance, Cnut gave his widowed sister, Estrith, to the duke in marriage but Robert repudiated her and there is early, though by no means conclusive, evidence that he planned an invasion of England on behalf of the two exiled princes. It is at least clear that there could have been no established friendship between the English and the Norman courts for some years before Cnut's death.

Cnut and his wife, Emma, were to become prolific givers of relics, manuscripts, land, textiles and other similar treasure. An image that Cnut was careful to develop as part of his need to shake off his past as a pagan, to gain respectability within Europe as well as England as a civilised, Christian king. He was to be the first Viking to be readily admitted into the fraternity of European Christian Kings - being made welcome even within the holy sanctity of Rome.

Emma is widely remembered as a most generous patron, giving to the Church at Ely, Abingdon, Winchester and Canterbury among others. Even to her brother Robert, Archbishop of Rouen, she sent an English Psalter. England was still reeling from the years of peace-buying from Cnut and his father's savage raiding, the Church had a great need for neglected rebuilding and the replacement of valuable artifacts, ornaments, books and vestments. Cnut's high testimony of patronage was most certainly as a mark of restitution - and as a public announcement of his altered status from that of ruthless invader to generous king.

For Emma, her patronage ensured that she was to be remembered with respect and affection in all those places that had been beneficiaries of her generosity. The artist who produced a drawing for the Liber Vitae of Hyde Abbey of Cnut and Emma giving a magnificent gold alter cross, depicted both king and queen in regal splendour. Emma herself is directly converged with the status of Mary, who is standing above her.

Queen Emma and King Cnut present a gold cross

to the New Minster, Winchester

The drawing, in conjunction with the praises sung for Cnut's various generosities, epitomize the feelings of goodwill that were offered to him as King of the English. Foremostly, the presence of one of the greatest Danish warriors in England guaranteed peace and prosperity through a respite from external attack.

Following the death of his brother in 1018/19 Cnut also became King of Denmark, adding Norway by 1028. The delegation of authority in England went to his earls - and queen - his responsibilities abroad heightening political responsibility for members of the Anglo-Saxon nobility.

Page 11

In 1017 he divided the whole of England into four areas, placing three under the authority of earls, and retaining Wessex for himself. The Danish title jarl - earl replaced the Old English ealdorman. Mercia went to Eadric Streona, Northumbria to Eric of Hlaðir and East Anglia to Thorkell the Tall, but before the end of the year Eadric Streona and several other noblemen, whom Cnut evidently mistrusted, were either murdered or executed. By 1018, Cnut had relinquished his own hold over Wessex by placing Godwine Wulfnothsson as its earl. Godwine's father probably being Wulfnoth, the same man who in 1008 was accused of treason while serving in Æthelred's fleet.(27)

Earl Godwine was to eventually become one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. Five of his six sons became earls. His daughter, Edith, was to be Edward the Confessor's queen, and his second eldest son was to eventually be crowned and anointed as king himself. His relationship and alliance with Cnut was ratified when Godwine took the Danish born Gytha as wife. Her brother was the first husband of Cnut's sister, Estrith, mother of Swein, who was to eventually follow Cnut as King of Denmark.

Cnut's rule of three different kingdoms inevitably led to several absences. Earl Godwine the most trusted of Cnut's earls, being placed as regent. Regents undertook to oversee the issuing of a king's orders during his absence, if he were still living or on behalf of a minor if the heir was too young to rule. The main claimants to the role of regent were usually kindred, uncles, brothers and such, but a plethora of male relations could in itself upturn the apple-cart, as William of Normandy discovered when he became duke as a child. Too many men were chasing the one prize, the result being intrigue, plot and murder. The unswerving loyalty of relatives on his mother's side, and later his own impressive skills as a warrior and leader, were the attributes that saved William from a young man's grave. The position of a powerful - or at least ambitious - mother, could be an ideal one in as far as protecting the rights of a son.

The annals of Winchester claim that Emma was regent during Cnut's absences abroad, quoting a letter sent by him, but they are late and are often much confused.(28) There is no conclusive evidence that women were respected in the capacity of regent in England, although, after Cnut's untimely death in 1035, Emma was at least in Wessex, regent for Harthacnut in 1035-7, who was at that time ruling in Denmark on behalf of his father, while Harold I, Cnut's "illegitimate" son, held the north.

The situation of Cnut's successor had not been adequately settled during his lifetime, not everyone in England recognised Harthacnut as the next king, let alone Emma as regent. The backing of Earl Godwine - at the outset - and the supportive action of the housecarls substantiate that Emma's claim was taken seriously, but whether she ruled Wessex as regent or as a dominant widow taking care of her dead husband and living son's lands is open to debate. Whatever the state of her capacity, it ended in 1037 when Godwine and men of his kind altered allegiance to Harold who subsequently took possession of Wessex, the royal treasury and the crown.

27) See above Page 5

28) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith p.188

Page 12

When Harthacnut eventually became king after Harold I's unexpected death only a few years later, Emma's role was ended. He was somewhere near eighteen years of age and had already been successfully ruling Denmark as King.

Prior to Cnut's death, however, whatever traditions were in place in England, when Norway came into Cnut's possession, Ælfgifu was sent to Norway to rule as guardian for Cnut's eldest son, Swegn. The regency was a disaster. Her failure was mostly due to autocratic harshness in attempting to implement high taxation, an intolerable burden of public service and severe penalties for violence. Norwegians were a fiercely independent people who immensely resented her attempt to introduce customs from Denmark into their lifestyle. By the autumn of 1035, after only five years, she and her son were forced to flee into Denmark. When Cnut died a short while later, Magnus Olafsson was already accepted as King of Norway. Swegn himself died at around the same time and therefore made no part in the ensuing dispute for England.

Cnut's reign was to last no longer than twenty years. He died, probably aged around forty, at Shaftsbury on the 12th November 1035 and was buried at the Old Minster, Winchester. The kingdom was to be seized by his son Harold by his first wife, and Emma was forced to flee into exile. There is no contemporary English account of the intricacies of Cnut's reign. Emma herself was to provide that in the Encomium.

Probably written by a Flemish monk c 1041/2 during the reign of her son, Harthacnut, and after Edward's return into the family. The Encomium "was a point of triumph, [for Emma] if not a height of power as the mother of kings."(29)

The work was dedicated to Emma, and it seems probable that the writer worked closely with his patron. It is not an autobiographical work, for although she is widely praised, she is not placed as the central character, only coming into the foreground in the latter part. The Encomium concludes as a celebration of a mother and her two sons, united in common cause - an image deliberately constructed. Cnut's death had plunged England into yet another struggle for the throne, into suspicion, disorder and uncertainty. Emma had been a central pivot throughout the past years as wife to the two kings and then being caught between the three claimants to the throne, Harold I, Harthacnut and Edward - four, if the murdered Alfred was to be included in the memory of a suspicious populace.

29) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith p.29

Page 13

Adding to the accumulating questions and difficulties of Cnut's heir, her ally, the powerful Earl Godwine of Wessex had also been implicated in Alfred's murder, and had been a man known to change allegiance at his own whim. Her own future was far from certain or settled. The Encomium was undoubtedly intended to clarify the situation, to influence by reviving the more glorious aspects of the past. Pauline Stafford, in her work "Emma and Edith" proposes that the Encomium was directly aimed at her sons and the influential men of England, the earls and the nobility. "It was a political work, from a political woman in the thick of politics."(30)

The succession of father to son is today accepted as the norm, but primogeniture was not the case in Anglo-Saxon England. The Ætheling, or heir, was the man deemed most suited to become king - often a son, but not necessarily so, and certainly not always the eldest born. Accession did not always pass unchallenged and too many heirs vying for a crown continued to cause problems until William of Normandy took England in conquest and introduced the right of accession, although even this caused squabbling and jealousies between a brood of brothers, and confusion if there was no male issue - the civil war between Stephan and the Empress Maude (Mathilda) and the fractious arguments between Henry II's sons as good example.

Edward the Confessor died without producing an heir, other kings produced too many by too many different wives, such circumstances provided the respective mothers a considerable opportunity to use and wield power both for their sons and themselves. A power that was, perhaps somewhat fragile, but then, so too was that wielded by the men.

At least the life of a woman was more protected than the male. Royal women who needed to be set aside had a better chance of surviving by being sent to a convent or married off to someone else. The men were, more often than not, simply murdered.

30) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith p.29

Page 14

The Dowager Queen

Cnut's first wife, Ælfgifu of Northampton had borne him two sons. One of these, Harold Harefoot, was the only son in England at the time of Cnut's death. Realizing his opportunity, he collected the support of the nobles and in 1037, was crowned King.

The clearest narrative of events after Cnut's death come from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, manuscript C. It tells of the dramatic wickedness of the usurper, Æthelred's illegitimate son Harold, of a prince's barbaric murder and the deprivation of Emma herself, driven into exile during the ravages of winter, but ending with the glorious ascent of Edward, the rightful heir, to his throne in 1042. It is a noble tale of a mother and her sons, of the triumph of good over evil, right against wrong. The telling recounts her role as a royal queen, the whole, sympathetic to her hopes and fears as a mother, to her dignity and rights as an anointed queen.(31)

Another version, manuscript E, is a less coherent narrative, focusing on the bitterness of dispute. Emma's role is more simply that of the mother of Harthacnut and widow of Cnut. His other wife, Ælfgifu, has her own place in this telling. Where she was dismissed roughly in manuscript C, she is here named as the daughter of the ealdorman, Alfhelm. Here, the rights and wrongs are not made so obvious, and Emma's position not so justified or applauded.

Various documentations may disagree over the individual slant of the writers, but do at least converge in agreement in the confirming of Emma's importance. The differences of opinion in these two chronicles, however, do enhance the need for caution in judging Emma's actions and situation.

Harthacnut, appointed King of Denmark by his father, could not leave as Norway was too much of a threat to Danish security. Emma remained in Winchester, apparently elected as regent and guardian of the royal treasury until matters could be settled by the noblemen who were heatedly divided over who should rule.

There were, however, two other claimants for the throne - the Æthelings Edward and Alfred. In 1036 they returned from Normandy, supposedly to visit their widowed mother. Alfred was captured by Earl Godwine of Wessex who handed him over to Harold's men. Alfred was taken to Ely and brutally blinded, where he died of his wounds. Edward, meanwhile, fled back to Normandy. Harold seized the treasury and Emma fled to Bruges - where she commissioned the Encomium to be written and promptly set about securing the English throne for her son Harthacnut.

31) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith p.9

Page 15

The Encomium blatantly sets about determining that Harthacnut was, and always had been, Cnut's favoured heir, not Harold. The introduction, after mentioning King Swein appointing Cnut as his heir, states, "there would scarcely have been an end to the fighting had he [Cnut] not at length secured by the Saviour's favouring grace a matrimonial link with this most noble queen." and goes on to say, "he had a son Hõrthaknútr by this same queen and while still living he gave him all that was under his control"(32)

The story is of Emma's Danish family, unfolding within the era of Scandinavian rule, not with her Norman birth or English connection. It starts with Swein's bringing of the fleet to England in 1013, goes on to tell of Cnut and Edmund (Ironside) of the north, of men skilled in council but equally so in treachery. God saves the English from years of fighting by disposing of Edmund. The tale is more than half completed before Emma herself makes her cued entrance. Her betrothal to Cnut is to bring peace and harmony once again to England's realm. She is a woman both beautiful and wise, rich in lineage and wealth. Gifts and implorations are sent to woo her to Cnut's side, but she refuses to agree, "unless he would affirm to her by oath that he would never set up the son of any wife other than herself to rule after him"(33) A shrewd move on the part of a bride who knew that her prospective husband already had a first wife who had borne him sons! The account describes Emma as a free-thinking woman in her own right. No negotiations with kindred is mentioned, all is done and arranged through her own speaking. She is asserting her own authority and prestige, an equal to Cnut and expecting to be treated as such. To share in his rule of England and for her sons by him, should there be any, to take precedence over any other. It was through her that war would be ended, as the role of wife is to be that of the family peacemaker, so the part of queen is to bring tranquility to the kingdom.

When Harthacnut is born, their joy is complete. He is kept by their side while other sons are sent for their education into Normandy. Edward and Alfred's exile is thus explained. There is no mention that they are the sons of a different king.

The finale of the story comes with Cnut's death and the years 1035-41 when the Encomium was being written. The lady is alone, grieving for her lost lord, anxious for the absence of the two abroad in Denmark and Normandy. The English have forgotten them all, deserted the sons and abandoned their loving queen, choosing above them a man who alleges himself to be the son of Cnut by a concubine. It is Harold, the Encomium asserts, who wrote a wicked, forged letter to Edward and Alfred in Normandy, declaring that their mother must send for them. So lured, the youngest son comes to England. He is received by Godwine, who in all good faith escorts him to Guildford, dispersing his followers among various lodgings. Harold's own men appear, deprive Alfred and his retinue of arms and condemn them all without a hearing. The prince is portrayed as a heroic martyr, the details of his tragic death unwritten to spare the anguish of his mother's grief.

32) Encomium Emmae p.7

33) Encomium Emmae p.33

Page 16

The letter is quoted in full,(34) the details of the event, aside from Alfred's suffering, also dealt with in full, Harold's deception made much of. Alfred had died an abominable death, there was an incriminating letter to be explained and suspicious questions to be answered. Harold had to be shown as a godless tyrant, Emma - and Earl Godwine who had by now again changed sides from previously supporting Harold to Harthacnut - to be entirely innocent. Her own flight into exile had also to be explained, why had she not stayed in England to fight for her sons - or to die for her beliefs? To save her dignity, the writer explains, to go where she can lodge in surroundings befitting a queen, and from where she can send, in safety, to Edward her son in Normandy and to Harthacnut in Denmark.(35)

The Encomium is a royal saga, telling of the reign of England by Swein and Cnut and of the horrors that followed his death, an outright justification of the legitimacy of Harthacnut's claim.(36) It establishes the remembrance of loyalty to the anointed king, to his legally taken Christian wife, the Queen, and to their produced son. It may also have been intended to discredit Edward's claim to the throne. In the final pages Emma clarifies why it was Harthacnut she returned to England with, not Edward, her eldest born. It was Harthacnut who Cnut had expected to be his heir, he who had the ability to restore England to peace and sense, and his mother to her dignity. Emma clearly doubted that Edward would be able to do any, if not all of these things. Her son by Cnut was the true heir, but as it transpired, he was not forgetful of his brother, it was he who reunited the family, he who decreed that the rule was to be shared, not divided. But then, was that the part of a shrewd move by either son or mother? Harthacnut, as yet, had no male heir and may already have been fatally ill.

When Harthacnut sent for Edward to be returned from Normandy in 1041, the fact of Emma's Norman birth seemed of marginal importance. Her role was incorporated into the identity of being a mother of kings, a member of a united royal family. Both Harthacnut and Edward were expected to produce heirs. The turmoil of events of 1066 were far off and unimaginable. But fate was to deal Emma a cruel blow. Harthacnut died suddenly in 1042, leaving Edward as the only possible heir to the kingdom.

34) Encomium Emmae p.41

35) Encomium Emmae p.47

36) The facts of its historical accuracy may be questioned, but the value of its content lays within its portrayal of character. Cnut is a political figure, not a Viking warrior as his father is shown to be. Emma herself is shown with many colours; her hatred of Aelfgyfu, her scheming and plotting, her despair and ambitions.

Page 17

For whatever reasons, Edward and his mother were not compatible. In 1043 he deprived her of all her land and wealth, and although she was restored to favour in 1044, she then declines into the background.

When Edward entered into exile after Cnut conquered England, he was an ousted prince with little hope of ever seeing a glimpse of the crown that might have one day been his. Prospects of making a victorious return against a warlord such as Cnut were highly unlikely. How he felt at his mother's marriage to his father's usurper is unknown. Had Emma done everything humanly possible to exert his claim? Or did she plan only for her own salvation? With prospects of a long, ignominious and lonely life, probably within the walls of a nunnery or a choice of remaining an exalted queen of England? When Cnut became king, "whatever may have been the terms on which Emma married Æthelred, much was changed since then and Emma's interests had altered."(37)

There was, in fact, very little that she could have done for her son in 1016/17.

It is also possible that Edward was not an ambitious young man, or that he was able to inspire others to fight for his cause. Given that in later years he was to turn more to ecclesiastical leanings, with his building of Westminster Abbey, piousness and apparent celibacy, it would appear, perhaps, that at the time of Cnut's conquest, he may have even been more inclined towards a possible career within the church. It is also possible that he was homosexual.

Whatever occurred between mother and son in 1016/17, twenty years later, the atmosphere between them was distinctly ice cold. Emma was to become a politically astute and wise woman as wife to Cnut, she was educated, literate and intelligent - it is assumed she herself commissioned the Encomium Emmæ Reginæ, "but whether she did or not, such a book would be a poor sort of compliment to a woman who could not read it."(38)

Did her first husband's ineptitudes frustrate her as much as they did his noblemen? Harthacnut was the son of the husband she must have at least respected, if not necessarily loved, she kept him at her side. Edward spent most of his life abandoned in Normandy. Barlow states "that he punished Emma for her neglect as soon as he was crowned king proves the long grudge. Edward always behaved like one who had been deprived of love."(39) An observation which to a modern day psychiatric doctor would go far to explaining many of Edwards later "quirks", not least of all his refusal to consummate his marriage to Edith. He clearly continued to blame Earl Godwine for the death of his brother Alfred, how much blame, one wonders, did he also lay at his mother's feet?

37) F.Barlow: Edward the Confessor p.37

38) C.Fell: Women in Anglo-Saxon England p.103

39) F.Barlow: Edward the Confessor p.38

Page 18

Lady. Wife. Mother. Queen.

Queen Emma died in Winchester on 6th March 1052, her death occurring during a period of great political upheaval. The recording of any queen's death in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written pre-1066 was rare, that Emma's passing is stated indicates her importance to her contemporaries. Edward had just faced the possibility of a civil war and the exile of the most powerful and influential earl in the kingdom, Godwine of Wessex, whose daughter Edith was Edward's wife. Edith, he had set aside, sending her first to Wherwell then Wilton abbey. Come September, Godwine was to return and challenge the King into full restoration of his and his family's lands and rights.

Emma's demise of 1043 had also been remarked upon in the Chronicle, a significance in itself of her position, and possibly, of the affection within which the Church held her.

Æthelred's mother, Ælfthryth was crowned and anointed as queen thirty or so years before Emma's arrival in England as part of the Imperial Coronation of her husband, Edgar. While the new-crowned King Edgar sat at the coronation feast with his bishops, ealdormen and all the dignitaries of England, his queen, clothed in fine linen, with jewels and precious stone embroidered overgarment, entertained the abbots and abbesses. The Benedictional of Æthelwold, a masterpiece of Saxon illuminations was a manuscript that placed an emphasis on royalty, and especially the role as Mary as a queenly image. Queens were probably consecrated before Ælfthryth's coronation 973, but either the ritual was rarely used, or there was no significant context for it to be used. "The unification of England and the growing power of its kings expressed an ideology shaped by religious reformation provided that context."(40)

The queen signing and witnessing charters at the beginning of the 940's signified her inclusion in the administration of lawmaking and government. During Cnut's reign Emma's signatures first appeared beneath those of the abbots, later rising to just after or in conjunction with the king's, indicating her rise in status.

Queen Emma, with her sons Edward and Harthacnut,

being presented the Encomium Emmae Reginae

(from the Encomium Emmae)

The Encomium shows how important the role of the queen was to Emma's self-respect and dignity. The copy of the manuscript intended for her personal use had royal names capitalized, highlighted or marked in half uncials - especially that of her own name. The book begins with an illustration of herself as the crowned, enthroned queen, the author is kneeling at her feet and her two sons are standing, half bowed behind him. (the manuscript is damaged, hence several holes)

This is one of the first illustrations of a seated royal figure, her poise and dignity enhanced. The author does indeed flatter his patron, but it is not a mere work of unadulterated praise. It was commissioned to expressly justify her actions and explain her circumstances. The work indeed shows her to be a royal and regal queen, but also lets us glimpse a woman, wife and mother with everyday tensions, anxieties and swaying loyalties that, through the necessity of unfolding events, pull her in opposing directions. Politics determined the story-line of the Encomium, dictating the priority of Emma's Danish connection, not her marriage to Æthelred. Had it been written a few years later, after Edward's coronation in 1043, perhaps the slant would have been different. Her commissioned story was not one of an elderly woman's tranquil reminiscences, but one of political necessity, stressing her perception of queen-wife and queen-mother.

The drawing depicting Cnut and Emma donating the cross to Winchester, on page 10 above, is thought to be contemporary. Given the rarity of a queen's portrait at this date, it is indicative of Emma's high royal status. In her work Medieval Women, Henrietta Leyser quotes T.A. Heslop's "The Production of De Luxe Manuscripts and the Patronage of King Cnut and Queen Emma, in Anglo-Saxon England" (1990 ed p.157) by remarking that he has observed that "It may also be significant that it is Emma who stands on the Dexter side of the cross, that is to say, she is at the right hand of Christ."(41)

The power that Emma as queen could wield for herself was already mapped out in the rules of tradition and expectation of early Medieval England and Europe. Pauline Stafford, in her work Queen Emma and Queen Edith, compares the role of these two women as to characters in a play. The script is there, written out, but the actor's must perform to personal interpretation, ad-lib their way through certain crucial acts of the play, as had several of their predecessors. "Emma's 'wife', 'queen' if not 'mother' and Edith's 'widow' were surely among the great individual performances of the English early middle ages."(42)

40) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith p.164

41) H.Leyser: Medieval Women p.79

42) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith p.55

Page 19

The queen's titles used in tenth and eleventh century documents were varied; Domina/hlÆfdige - lady, Regina - queen, conlaterana regis - she who was at the king's side, regis mater - king's mother, and were often paralleled to the Virgin Mary, the Queen of Heaven, Christ's Mother. The Lady (seo hlÆfdige) was how Emma was described in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle when first she came to England as Æthelred's young bride, and when she died, again, she was so called. The Latin regina, (Old English cwen,) is a link between king and queen - how far the title extended to the sharing of a king's attributes and powers is not known. The acquisition of rex transformed the status of a man for all time, but regina did not do the same for his wife. Once her husband was dead she could only became king's mother if she were fortunate enough for her son to succeed to the throne.

The king, in old English, cyning, was both ruler and head of the family. In theory, kings were born to the blood line - those who were not soon found a way to legitimacy - queens only acquired the part by marriage. The idea of a queen being independent of the title "kings wife" was contestable in the latter years of Anglo-Saxon England. All others were identifiable titles, regina sometimes appearing as no more than the consecration of an especial wife or mother, however, the consecration of a queen did change the immediate status of the woman so consecrated.

Once anointed she was no longer just a wife or mother. Emma was a consecrated queen, crowned at the time of her marriage to Æthelred in 1002. The basic rites used for Ælfthryth's coronation were used for the making of an English queen until the end of the eleventh century. Cnut's consecration was to be especially important. He needed to emphasize his "Englishness", was to be consecrated in the time-honoured, traditional way to emphasize continuity, to detract from the fact that he was a conquering foreigner. His chosen queen's symbolic role, even more so.

Page 20

Emma was to be the peace-weaver, an English queen of Norman/Danish birth, already once anointed, preparing to undertake a partnership with England's new sovereign, a partnership of unequivocal unity. For these reasons Emma was almost certainly consecrated a second time. She was acceptable to both Cnut and the English, her role stressed as a partnership for the benefit and well-being of England. "There was to be no doubt that the queen of the English now married to their conqueror was to be a sharer in his power and rule."(43)

The king's household was comprised of churchmen and warriors, the military and administrative functions required of them attracting men of wealth and nobility. A household that surrounded the king was the centre of his kingdom, consisting of all those who personally served him in a variety of capacities coming to court in rotation, or when he happened to be in their area. In Domesday, a king's thegn was, literally, a king's servant although not always necessarily engaged in actual service. Some of his servants could be of humble origin, many of his officials were the greatest men of the realm. Although cities such as Winchester, London and York were of prime importance, they were not capital cities, for the capital was situated where-ever the king and his household happened to be residing.

The housecarls, the military element, provided the basis of a royal army to be used by express command of their king. The chapel, served by royal priests, housed any royal relics, and with the household, the centre of the economy, went the royal treasury. The royal palace at Winchester during the eleventh century served almost as a permanent treasury. Stories tell of a great chest of treasure in Edward the Confessor's private rooms. Whether trundled in huge chests around the country in the wake of the king, or residing at Winchester, the treasury was one of the responsibilities of the king's officials, especially, that of his chamberlain.

The structure of royal households can be glimpsed in the records of the Domesday Book, where there is a suggestion that the queen may have had a separate household of her own that ran parallel to that of the king's. For Emma, Winchester, her dower borough, held a prime importance, her household was centered on this administrative city.

After her fall from power in 1043 Emma retired to her own-held property there. In the eleventh century, her death was commemorated in Winchester, and in the twelfth, the house where she lived still remained identified as hers.

43) P.Stafford: Queen Emma & Queen Edith p.178

Page 21

The years of 1035 and 1043 are indicative of her holding of power within the royal household. In 1035-6 she was at Winchester with the king's housecarls, whether these were her own bodyguard, or part of the military army is unclear, what is certain is that she was in sole possession of the entire royal treasury, although her step-son, Harold I was to eventually forcibly deprive her of it. Again, in 1043 she was holding the treasury when Edward, forcing her into the status of dowager widowhood, reclaimed it from her keeping.