|

Page 1

The Roman historian, Cornelius Tacitus, began a biography of his father-in-law(1) towards the end of AD 97, and because of this work, one of the few surviving records of the Roman period, the career of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, Governor of Britain for almost six and a half years, is more thoroughly known than any of his colleagues.

The work must be regarded as biased, claiming, as it does, the virtues of a man who is a heroic member of the immediate family. One important omission from Tacitus's Agricola, annoyingly, is the absence of dates. Fortunately, Agricola's campaign in Northern Britain does not entirely owe its kudos to having a distinguished writer as a son-in-law. The subsequent archaeology of his march northward confirms that he was an adept and capable commander.

One result of the Roman attempt at conquest of the northern lands that eventually came to be known as Scotland, was the recorded naming of the indigenous tribes. Writing in Alexandria in the second Century AD, the Greek, Ptolemy, included sixteen tribes of this area on his map, adding alongside, settlements, rivers and several geographical features, information that would never, today, be discovered by the archaeologist working in the field.

There is no conclusive evidence of the political boundaries of the inhabitants of the north with whom the Romans came into contact - tribes such as the Votadini of south east Scotland; the Selgovae, central southern Scotland; the Novantae in the south west; the Damnonii of the Strathclyde area, and the Venicones of Fife. So effectively did the warriors unite against the machine that was Rome, that classical writers referred to the northern tribes as "a single ethnic group, the Caledonians", their country as "Caledonia".(2)

Page 2

Ptolemy, interestingly, does refer to the Caldonii, locating them in either the Great Glen or the Grampian massif.(3)

The area roughly corresponding to the present counties of Cumbria and Lancashire, was occupied by the Brigantes. It is possible that their lands also stretched northward as far as the Solway Firth and the Tyne.(4) The Roman subjugation of Brigantia, the occupation of the southern uplands of Scotland, and the advance even further northward, occurred between AD 71 - 84 under the command of three successive Governors of Britain, Petilius Cerialis, Julius Frontinus and Julius Agricola, the latter, completing the Briganlian conquest in AD 79 and continuing northward, moving as far as the river Tay. His route is unknown, but he must have either moved up Annandale and down Clydesdale - following the present route of the A74 - or along the east coast, today's A68. Or perhaps he used both.

Whatever route, he passed through the areas of several tribes, notably, the Votadini and Selgovae, seemingly encountering little resistance, but, ,2 "not without learning that in these remote areas the climate could prove as formidable an enemy as any other that might be encountered."(5)

This advance, achieved so rapidly, was secured by the establishment of garrisons placed at strategic points, and incorporated the narrow isthmus between the Firths of Clyde and Forth. It is unclear whether Agricola's orders were to advance this far and halt, or whether, having reached that far, and acting on advice from the reconnaissance of scouting parties and local information, he decided that this would be an ideal, easily defendable line, a practical, natural, frontier. The Highlands to the north lay ahead, an inhospitable, sparsely populated area, of mountains, lochs and valleys, that did not draw much need, regarding the acquisition of trade, natural materials etc, to be conquered.

In southern Scotland, the geography would have dilated routes and the placing of garrisons to secure the land and tribes that Rome subdued. In each major river valley, Agricola built large forts, one placed in the Tyne valley, a fort of about 10 hectares, may have been used as a supply base.(6)

To the north, in the Tweed Valley, lay Newstead, (Trimontium) established on the north-west hill of the Eildons, below the oppidum of the Selgovae. This eventually became the pivotal point for the Roman road system in the area. On the Forth, there was Camelon; Milton, in Annandale; Dalswinton in Nithsdale and in Clydesdale, the construction of Casteledykes. Elsewhere, were smaller stations suitable for holding a single auxiliary unit. These, and the roads between them, formed a network common to any recently subdued Roman province, the only unusual feature of the Empire, being the frontier line of forts across the isthmus.

Page 3

In AD 82, Agricola turned his attention to the west, marching into Ayrshire and Galloway. He crossed the Solway by sea, very possibly leaving from secure winter quarters in Chester, and marched up a river valley, suggested to be that of the Nith.(7) After a series of clashes against the south-western tribes, he again established further secure forts have been identified at Loudoun, Gatehouse, Fleet, and garrisons. Agricolan Glenlochar. Evidence that the road system may have extended to the Ayrshire coast and the Rhinns of Galloway is scarce, but is a widely accepted proposition.(8)

Results of this campaign, however, may have been discouraging, for Agricola then returned to the Forth-clyde line. The ensuing pause at this frontier was reversed in AD 83. Normally, Agricola would have expected his term of office to end after three consecutive years, but he was, unusually, to continue as Governor for a further term of office. His two final seasons passed with him campaigning north of the Forth, probably at the direction of the new Emperor, Domitian.

The dangers of moving a single force along the eastern plain north-eastward to Stonehaven and then turning north-westward must have been great, for the terrain was unknown, and the inhabitants cc-operated together to form a force of resistance against the forward moving Romans to such an extent, that it was here that it was assumed the tribes of the north were one single native group - the Caledonians.

Agricola fought one opposing force which had attacked his ninth legion in a night assault, loosing one third of his men, the site of this camp is unknown. He also had lo deal with a mutiny by a recently raised regiment of troops from Germany. Tacitus remarks that Agricola divided his forces some time before this. A.A. Duncan suggests that, if this is reliable, then the division must have been in southern Scotland, reaching his conclusion by the identification of the size of subsequent marching camps. The lie of the roads, and the garrisons constructed beside them, through these southern uplands, seem to confirm that passage north was indeed made on two fronts, or at least, in two columns, one to the east, continuing a route from Piercebridge and Manchester and one to the west, from Carlisle.

Archaeological evidence supports Tacitus' writing. A great many sites, chosen by Agricola for the building of garrisons were in upland country, where disturbance by agriculture or building is rare. Although often difficult to interpret these sites by eye, air photography has discovered many locations, although some were only briefly used, marching camps. Agricola had a good eye for the placing of his garrisons, for many were re-used in the later Roman periods.

Page 4

The forts that he established between the Forth and the Clyde, cannot, now, be identified with any certainty', a once generally accepted view was that they were situated beneath the later structures of the Antonine Wall, but this opinion is no longer so widely agreed.(9)

Agricola built the road that is now known as the Slanegate, laying a short way south of the line followed by the later constructed Hadrian's Wall. The Tyne gap and the hills to the north, gave rise to conditions for a favourable frontier defense, and it was here that such a line rested for most of the Roman occupation, but in Agricola's time, such stability had not been reached, and it must have been expected, during these early years, to continue the advance north and conquer the whole island into a single Roman province.

Agricola's army moved along the road running from Corbridge to Risingham, High Rochester and Chew Green, the last a site for an encampment that must have been, more often than not, mist shrouded and snowbound during the winter months. It is curious why this route was chosen, as the difficulties in keeping the roads open and the garrisons adequately supplied, must have been problematic - an easier route would have been along the coast. From Chew Green, the road passed to Newstead in the Tweed valley, and finally down to the Forth at lnveresk, after crossing yet another stretch of high moorland. Hunter Blair suggests that it is here that the two divided columns re-met, as Interest is also where the road running up the western side of the southern uplands terminates, after coming up from Carlisle and climbing up via the Beattock Summit before descending into the valley of the upper Clyde. Higher than the Fodh-clyde isthmus, there is only a single road heading northward, crossing the Forth at Stirling, and then north-east to Strathallan and Strathmore, a wide fertile valley between the Grampians and the Ochil and Sidlaw Hills. Here, along this road, is the evidence of Agricola's planning', skillfully placed forts, camps and signalling stations, and including the legionary base of Inchtuthill. A series of marching camps lead on across Aberdeen, almost reaching the Moray Firth.

It was somewhere here, the exact location unknown, that Agricola fought and took victory at the only battle to be described in detail in ancient literature, between the Romans and the Caledonians (the Picts). Mons Graupius - the Graupian Mountains. An eighteenth century misreading of this battle gave rise to the modern name, the Grampian Mountains.(10)

Using common tactics, while the army marched light, Agricola sent the fleet ahead, to spread alarm among the tribes, and to plunder where and when they could.

Page 5

The tribes made preparation for the battle, using ground of their own choosing, and setting aside their own differences to unite against a greater and more threatening opponent. This was an unusual treaty, given the more general aversion of the British to fight together against a common enemy. Only one of the leaders do we know by name, Calgacus.

Tacitus informs that there were more than 30,000 barbarians straddling the hillside, with the van situated on level ground at the bottom, and the rest rising up the slope behind. He does not state the number of Romans, apart from mentioning that there were 8,000 auxiliary infantry and 3,000 cavalry, with an additional 2,000 cavalry as reserve.

Presumably, all four of the British Legions were present, though undoubtedly in much lower strength. Tacitus's flair for imaginative writing presumes much inaccurate detail, including fanciful, florid speeches made by the commanding officers.

The order of battle followed common methods of the British tribes, charioteers galloping between the lines, and the fighting beginning with a mutual exchange of missiles. When the Romans began to advance, the British were at considerable disadvantage, for the Romans were armed with their shod swords and shields, while the Caledonians had smaller shields and longer, slashing swords, not so suited to close combat. Those tribesmen assembled along the plain were quickly routed and pushed back, up hill. The speed of the advance, however, almost caused disaster for the Romans, for now, they were faced with an up-hill struggle, and with the cavalry joined in battle, the infantry almost fell into disarray. The Caledonians, on the more advantageous higher ground, began to advance, and almost managed to overwhelm the Roman rear, but the attack was broken when Agricola sent in the four ranks of Cavalry reserve. With the Caledonians faced by Romans on both sides, they broke rank and fled to the wolds, where they briefly rallied, but were of no match to the high discipline of the Roman army.

Again, the figures mentioned by Tacitus, are undoubtedly fictitious. 360 Romans lay dead, he claims, compared to 10,000 Caledonians, although by "Romans" he could have been referring to actual Legionaries, not the auxiliaries.

Agricola made no attempt to follow the fleeing Caledonians, but prepared instead, to return south. Collecting hostages from the Boresti, an unknown and unlocated tribe, he ordered the fleet to sail while he marched south. During this voyage, the fleet discovered Orkney and the Fair Isles, and proving, that indeed, Britain was an island.

The location of Mons Graupius is left to conjecture, with several opinionated suggestions being put forward at various times. Gordon Maxwell, the Director of the Aerial Survey Programme with the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, with his work, A Battle Lost, Romans and Caledonians at Mons Graupius, collates the various antiquarian theories providing an interesting read.

Page 6

The location was undoubtedly north of the Forth - the line of first century marching camps appear to reach as far north as Auchinhove, making it possible that the battle site was north of the Mounth, where the Highlands reach almost to the coast at Stonehaven.

Victory at Mons Graupius was not conclusive to the Roman subjugation of Scotland, however, for none of the Agricolan forts north of the Forth were occupied for very long, indeed, judging by pottery evidence, all garrisons north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus were abandoned by AD 90. The Inchtuthill fortress was abandoned even before it was completed, and excavation at two further sites, Fendoch and Cardean, "has demonstrated that they were given up after brief occupations."(11) The construction and occupation of about twelve forts is, therefore, squeezed into ten brief years. Besides Tacitus, there is no literary evidence and archaeological evidence cannot be relied upon to confirm dates during such a brief time, therefore, the "history" of the high lands, north of the Forth, must be designed by the ideas of logic and by using

Tacitus as a general guide only, knowing his report to tie aided by fancy and exaggeration. Agricola was recalled to Rome soon after Mons Graupius. After serving as Governor for seven campaigns, he clearly believed that he had defeated the Caledonian tribes. His success was short lived possible because Rome had to withdraw part of its Legions from Britain in AD 87 or 88, forcing many of the forts beyond the Cheviots to be abandoned.

By the end of the century, the Roman frontier of Britain lay along the Tyne - Solway isthmus, the status quo being established in AD 122 or 123 by the Emperor Hadrian and his construction of a great wall.

Sources:

Alan K. Bowman

Life & Letters on the Roman Frontier

British Museum Press 1994

David I. Breeze

The Northern Frontiers of Roman Britain

Batsford (reprinted) 1993

T.A. Dorey (ed)

Tacitus

London 1969

A.A. Duncan

Scotland, the Making of a Kingdom

Mercat Press 1996

P. Hunter-Blair:

Roman Britain & Early England 55 BC - 871 AD

Cardinal 1975

Anne Johnstone:

The Wild Frontier: Exploring the Antonine Wall

Moubray House Press 1986

Gordon Maxwell:

A Battle Lost: Romans & Caledonians at Mons Graupius

Edinburgh University Press 1990

R.M. Ogilvie & I.A. Richmond (ed):

Cornelii Taciti, de vita Agricolæ

Penguin Classics

Anna Ritchie & David I. Breeze:

Invaders of Scotland

Edinburgh H.M.S.O.

Peter Salway:

Roman Britain

Oxford - Clarendon Press 1981

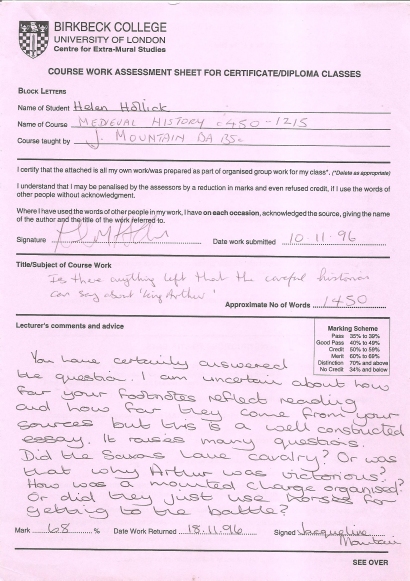

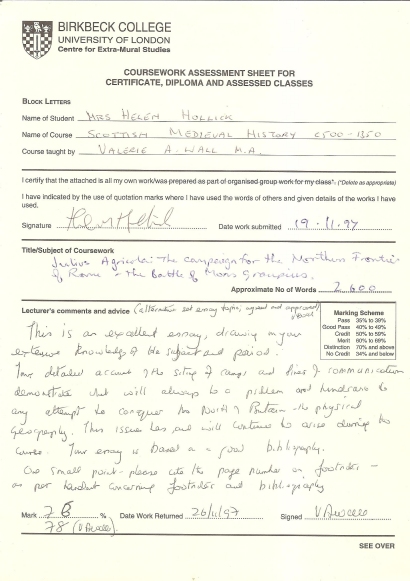

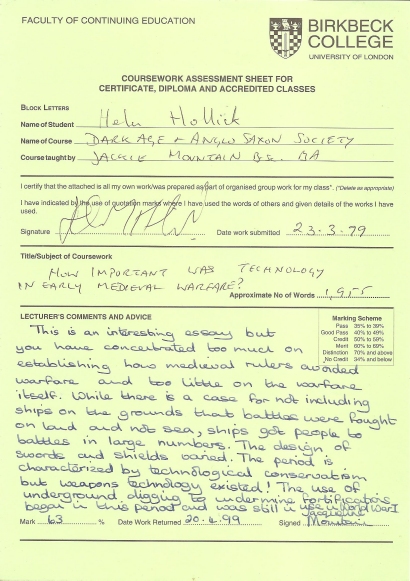

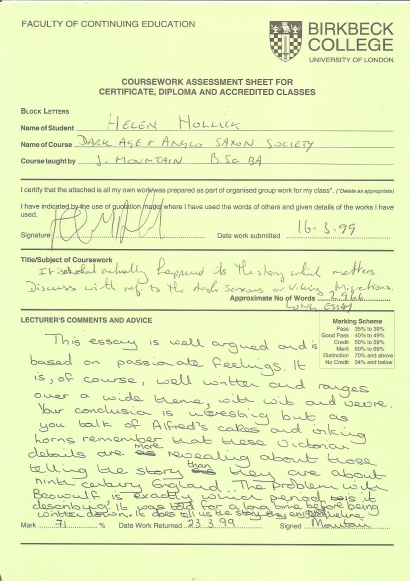

Assessment

" This is an excellent essay, drawing upon your extensive knowledge of the subject and period. Your detailed account of the siting of camps and lines of communication demonstrate what will always be a problem and hindrance to any attempt to conquer the North of Britain - the physical geography. This issue has, and will continue to arise during the course. Your essay is based on a good bibliography. "

78% 26.11.1997 V Wall M.A.

|

"Harold the King"

"Harold the King" "I Am The Chosen King"

"I Am The Chosen King"