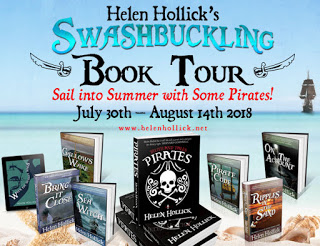

Blog Tour 2018

A voyage around the blogs, the topic being "Pirates!"

§

Charting the voyage

| # | Date | Blog Host | Topic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 30th July 2018 | : | Cryssa Bazos | Dropping Anchor to Talk About Pirates |

| 02 | 31st July 2018 | : | Anna Belfrage | Ships That Pass |

| 03 | 1st August 2018 | : | Carolyn Hughes | Pirates of the Middle Ages |

| 04 | 2nd August 2018 | : | Alison Morton | From Pirate to Emperor |

| 05 | 3rd August 2018 | : | Annie Whitehead | The Vikings: Raiders or Pirates? |

| 06 | 4th August 2018 | : | Tony Riches | An Interview With Helen Hollick |

| 07 | 5th August 2018 | : | Lucienne Boyce | Anne and Mary. Pirates. |

| 08 | 6th August 2018 | : | Laura Pilli | Why Pirates? |

| 09 | 7th August 2018 | : | Mary Tod | That Essential Element… For A Pirate. |

| 10 | 8th August 2018 | : | Pauline Barclay | Writing Non-Fiction. How Hard Can It Be? |

| 11 | 9th August 2018 | : | Nicola Smith | Pirates: The Tales Mixed With The Truth |

| 12 | 10th August 2018 | : | Christoph Fischer | In The Shadow Of The Gallows |

| 13 | 11th August 2018 | : | Debdatta | What Is It About Pirates? |

| 14 | 12th August 2018 | : | Discovering Diamonds | It’s Been An Interesting Voyage… |

| 15 | 13th August 2018 | : | Sarah Greenwood | Pirates: The Truth and the Tales |

| 16 | 14th August 2018 | : | Antoine Vanner | The Man Who Knew About Pirates. |

Cryssa Bazos "Dropping Anchor to Talk About Pirates"

They might, if you were lucky and kept your wits about you, share a bottle of grog (rum) though. And if you were very lucky, they wouldn’t shoot you during or after the merry-making!

Pirate

PiratePirates. The terrorists of their era – which was, primarily, a somewhat short ‘Golden Age’ centred around the Caribbean from about 1715– 1722ish, although piracy was known during the time of the Greeks and the Roman Empire and is still known (and feared) today, but hear the word ‘pirate’ and we automatically think of the Jolly Roger Flag, a gleaming cutlass, a bottle of rum and a swashbuckling life geared towards collecting as much (stolen) treasure as possible.

The image is partially true.

Pirates. What we think we know about them comes, on the whole, from the movies, TV and fiction. Who does not remember Captain Hook from Peter Pan, Long John Silver from Treasure Island, and of course Captain Jack Sparrow from the Pirates of the Caribbean Disney franchise?

You probably know a few of the factual names of real pirates as well; Blackbeard, Charles Vane, William Kidd, Calico Jack Rackham, Anne Bonny, Mary Read… You might also have heard of Black Sam Bellamy, Stede Bonnet and Howell Davis. Most of them hanged or died forlorn deaths – a pirate’s life was a short but merry one. Or was it as merry as we like to think?

It was certainly a hard life, but then life was hard for everyone who did not have the blessing of a good birth and access to the family fortune. In the early years of the eighteenth century the rich were rich, the poor were poor. (For the pedantic and picky people perusing this article, the same is true throughout history, but I’m waffling on about the 1700s, savvy?) Conditions were, well let’s not be gentle, very smelly, very dirty, very unhygienic and by our modern standards very unpleasant. Medical knowledge was limited, as was variety of diet.

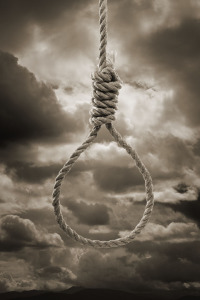

You worked from dawn until dusk for very little reward. If you were a woman you could expect to die in childbirth, and you were old at fifty – if you lived that long. Piracy was, for that short Golden Age, an attractive prospect. It was still a hard life, death was still a very real prospect courtesy the hangman’s noose, from injuries received, or severe illness from things like dysentery, plague, scurvy or sexually contracted disease such as syphilis.

But being a pirate meant a certain amount of freedom. They went where they liked, when they liked. They had access to relatively decent food and plenty of rum – albeit they had to find a ship to steal it all from first, and then go about actually acquiring it. The added bonus? They could end up rich. Very rich indeed if they happened across a Spanish ship taking a cargo of gold from Mexico to Spain, or a merchantman laden with a cargo worth a fortune when sold.

Some pirates did end up rich. Blackbeard did alright for himself, until the Governor of Virginia decided enough was enough and sent a Royal Navy crew out to put an end to him. Samuel Bellamy possibly became the wealthiest pirate. He had a reputation for mercy, gentlemanly and generous behaviour. Amassed a fortune but had a short piratical career of little more than a year. Born in Devon in late January or early February 1689, he drowned at the age of twenty-eight when his ship, the Whydah Galley, went down in a violent storm off the coast of Cape Cod. Perhaps he was one of the lucky ones. Most pirates, including William Kidd, Charles Vane and Jack Rackham, died on the gallows.

In most fiction tales where the pirate is the hero he escapes the noose - but that is the stuff of fiction. Reality is never quite so clement. However, fiction is about entertainment and for all their reality faults, the fictional pirates are always entertaining aren’t they?

Give me a made-up hunk of a hero pirate over a real, very nasty one, any day!

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Anna Belfrage "Ships That Pass"

I adored the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie, The Curse of the Black Pearl, (not the others in the Disney franchise; they ranged from okay-ish to terrible). I was enchanted by it, and not entirely because of Johnny Depp’s portrayal of Captain Jack Sparrow, although that certainly helped! The movie was fun. None of it was meant to be taken seriously and nearly every scene had a laugh attached to it. Laughter is good for us, therefore darn good adventures, be they pirates, Star Wars sci-fi, Game of Thrones fantasy or whatever-floats-your-boat, are good as well, whether movies or novels. They are also escapism from the daily grind, something we all need and enjoy.

Galleon

GalleonThe problem with really enjoying something is that you are then left wanting more. For me I wanted to read an adult novel - with ‘adult’ bits in it, if you get my drift - that was something similar to POC#1. In other words, a pirate-based adventure with a handsome rogue of a hero, a lovely leading lady, lots of swashbuckling – and a dash of fantasy. I couldn’t find anything.

There were lots of very good ‘straight’ nautical fiction - mostly aimed at male readers - and lots of young-adult sea adventures. Which were also good, but they were sans ‘grown up’ bits, well, sex. So I wrote my own novel. For adults. The result is my Sea Witch Voyages series. I wrote the first novel (and the other six, the seventh is in production) for fun: fun to write and fun to read (I hope.) But there came a spin-off I hadn’t expected from these novels about Captain Jesamiah Acorne and his loyal, patient, very understanding girlfriend, the white witch, Tiola Oldstagh.

I was approached by Amberley Press UK to write a non-fiction book about pirates. I was hesitant. Could I do this? Did I know enough about the ‘Golden Age’ of the early eighteenth century? The title was to be Pirates; Truth and Tales. That hooked me. I could write about the truth, the factual side of these mostly unpleasant men who were, to be blunt, the terrorists of their time, and balance this with the lighter side, the sea shanties, sailors’ superstitions, how they entertained themselves, how they acquired their ships (no guesses – they usually stole them.) And I could include fiction. The classic tales such as Treasure Island and Peter Pan with Captain Hook. Daphne du Maurier’s Frenchman’s Creek and a short excerpt from one of Anna’s timeslip novels.

"Hang on" do I hear you say, "Anna doesn’t write about pirates in her time-slip Graham Saga!"

That she does not, but she does write about indentured slavery, and several pirates started out as such before turning to a life on the High Seas. Explorer, navigator and privateer William Dampier was an indentured slave. So I included a short scene from Like Chaff in the Wind to illustrate the misery these poor souls were put through.

Anna and I had also written a very moving scene together for an Indie BRAG Book Blitz Week back in 2015. We wondered what would happen if my Jesamiah was to meet Anna’s Alex in 1661 as she was crossing the Atlantic in search of her husband, Matthew Graham, who had been abducted, transported to Virginia and sold into enforced labour. This is what we came up with:

Ships that pass

by Helen Hollick & Anna Belfrage

by Helen Hollick & Anna Belfrage

Somewhere in the Atlantic, 1661…

"Who are you?"Alex wiped at the wet hair that was clinging to her face. She knew for a fact she'd not seen the man standing beside her before on the Regina Anne - Captain Miles would never tolerate a sailor who looked so, so, dangerous? Her gaze slid over his cutlass - cutlass! - and the pistol tucked through his belt up to his dark eyes. He was grinning, his gold acorn-shaped earring glinting in a sudden flash of sun. Beneath his three-corned hat he had thick, black hair, tied back with a sea-blue ribbon. Poncy, Alex thought, but then men in the here-and-now had a predilection for lace and ribbons. Not like the men of her time, who thought they were daring if they wore a pink shirt with their business suit.

The man removed his hat, made a slight bow. "Captain Jesamiah Acorne, at your service, ma'am. And who might you be?"

Captain? Alex thought boats only had one captain. And this captain didn't exactly look like the sort of person Captain Miles would comfortably work alongside. Fight against maybe?

Swallowing another threat of rising bile, Alex attempted to be polite. "I am Mistress Alexandra Graham, wife to Matthew Graham who has been abducted and sold into indentured slavery."

"That was careless of him," Captain Acorne quipped, taking a small silver container from his pocket. Un-stoppering it and putting the spout to his mouth, he took a long swig of whatever was inside.

"It was not carelessness at all!" Alex bridled, angry, her fists bunching. "He cut off his brother's nose. In revenge, the bastard has had Matthew transported to Virginia to be sold into indentured labour - a death sentence. I am intent on not letting my husband die, either there or bound in chains aboard one of these, these," she whirled her arms around indicating the ship, "floating coffins!"

Acorne wiped the top of the flask and handed it to her. Alex shook her head.

"It'll do your stomach good." he said, offering it again. "And if his brother is anything like mine, I think I like the sound of your husband."

Alex took the flask, wiped the spout again with the corner of her cloak and took a tentative sip. Spluttered at the taste of very strong rum. He was right, though, it was warming. Tasted good. She had another sip, said quietly, "I cannot bear to think of Matthew chained in dark squalor below deck."

"Ah." Jesamiah Acorne nodded. "I've no liking for men who carry their enchained brethren like so much cattle across the sea. I've suffered such myself." He took the flask back, gulped a mouthful of the contents down.

"You have?" Alex supposed she should commiserate, ask him about his experiences, but the man just shook his head, indicating these were matters he refused to talk about. The deck tilted. It tilted again, and Alex clung to the railing, cursing the wind, the sea, the goddamn boat and, most of all, Luke Graham.

"I am no sailor," she admitted. "I hate this bloody boat. I hate picking weevils out of bread that is as hard as iron, I hate having no private place to relieve myself, no fresh water to clean my hair or teeth - to wash. Nowhere warm or dry to sit or sleep. I hate the squalor, the stink, the fact that the bloody boat itself is as fragile as a walnut shell and might fall apart the next time the wind blows up!"

"Ship," Captain Acorne corrected, "she's a ship."

He pointed to the masts soaring overhead into the grey-blue sky, the wind-filled canvas sails creaking and groaning, the rigging humming like a discordant, badly rehearsed string section of an orchestra. "Three masts, fore, main and mizzen. That makes her a ship, not a boat."

Ship's rigging

Ship's riggingHe leant back against the rail, looked about with a critical eye - completely at ease with the ship's perpetual rise and fall and roll motion. "Sails set fair, cordage coiled and stowed neat, decks clear and tidy." He pointed to a nearby hatch that had been partly swung open to let light and air down to the deck below; "Secured correct. Looks like this vessel has a captain who knows what he's about, and a crew not made up of mithering landlubbers who don't like to get their fekking hands dirty. She's smaller in length and width than my ship, and her quarterdeck is higher. I don't have any poop deck aboard Sea Witch. My father had a ship like this one when he sailed with Henry Morgan. She was a sound vessel, from what I gather. As fast as a greyhound. Regina Anne won't be as good if she needs a turn of speed, but she seems seaworthy enough."

"I don't care if she's not the bloody HMS Victory," Alex retorted. "As long as she's not the Titanic! I hate the sea. I hate the way it goes up and down; I hate the cold, the wet!"

He looked at her quizzically, not recognising the ships' names. "The sea can be fickle, I grant, and you must treat her with the greatest respect. She can be all those things, but the sea and a ship, to some, mean freedom and dignity. You treat sea and ship like a mistress, with care and attention. And you put up with their squalls and the tantrums for what they offer in return."

Alex nodded, pretending she agreed. For all the passion he was expressing, to her mind he was talking fool nonsense. She did not care a bent binnacle, or whatever the nautical words were, for this ship or any ship, and she had no idea why she was listening to this rag-tag ruffian. She had no idea who or what he was, although that cutlass and pistol reminded her of the appearance of a pirate. Whoever, whatever, she had a suspicion that he did not belong to this boat - ship. There was something about him, something different yet familiar? "He does not belong to this ship or this time," she thought. "Like me. He shouldn't be here."

Somehow that helped, and she suddenly found herself talking and talking, letting loose all the fears that had been churning, heavy in her stomach - and had refused to be spewed up over the side with her seasick vomit. It all poured out, the whole story of Matthew and Luke, finding a ship to take her as passenger, the misery of seasickness, the horror of it all and the fear that any moment may be her last.

Embarrassed at her outburst she ended with the truth. "What if this ship sinks? I'm scared shitless!"

He answered her with a smile and equal truth. "Ships do sink - more often than us sailors want to think about. Wind, tide, storms, current, they can all take their toll." He gave a low, deep-throated laugh. "And then there's pirates."

Alex decided to ignore his last remark. She had enough on her over-full plate as it was. "Not the ship Matthew is on." She gave him a despairing look. "Not the ship with my Matthew. His ship is sturdy and fast and safe. He is safe. He is!" Jesamiah, Captain Acorne, did not reply. He just looked at her, and something in his eyes made her want to cry. "He must be safe" she said. "Without him, I would die." Just like that, Alex bit her lip in an effort not to wail out loud.

The man, Captain, Jesamiah Acorne, put his arm around her shoulders and drew her to his side. For that brief moment Alex felt warm and comfortable. Safe. Despite the fact that he stank of unwashed clothes, sweat and tar. Matthew smelt the same, although without the tar. Tears of lonely grief filled her eyes, her heart and her soul.

"Believe in yourself, sweetheart," Jesamiah said as he kissed the top of her head, "and keep that vision of freedom in your mind. The blue sea, the white-capped rollers, the wind that is filling the sails. Touch a stay every morning for luck. And never give up hope. Once you do, you might as well head for the horizon with your arse on fire."

She blinked back the tears, shut her eyes, gripped the rail. When she opened them again, he had gone. But there, on the deck beside her foot, was a tightly stoppered silver flask, and, wound around it, a blue ribbon.

© 2018 Helen Hollick & Anna Belfrage

Carolyn Hughes "Pirates of the Middle Ages"

Basically, where there was trade and merchants shipping goods by sea there was piracy. That get-rich-quick lure of stealing something rather than working hard to get it.

Having said that, it was probably hard work to be a pirate back in the days of early sail. Those days of seafaring trade – from the Ancient Greeks, through the Roman Empire and the Vikings to the Middle Ages of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Those sailors – merchants, war ships and the pirates – had no compass for a start. No sophisticated rigging and sails. No cannons. No maps.

Trade was undertaken from safe anchorage to safe anchorage. With only a few exceptions, navigation was from visible point to visible point. These sailors braved the North Sea, the Baltic, the Mediterranean. No America as yet, Columbus didn’t open up that trade route until he ‘sailed the ocean blue in fourteen-hundred and ninety-two’, although it is strongly suspected that he knew where he was going and had charts and verbal ‘directions’ to follow. The Norse (the ‘Vikings’) did discover Iceland, Greenland and what is now Canada and the upper part of the East Coast of the United States – but there were no trade routes, so no piracy.

Nations as we think of them now were still evolving and in a state of constant flux in the 1100s, but whoever temporarily ruled as king, duke or emperor, piracy was always a thorn in their various royal backsides. Maritime supremacy by official navies was at an embryonic stage, with no ability or means to oppose wilful piracy.

Some pirates we know of were John Hawley from Dartmouth in Devon and Dorset-born Henry Pay, although they could be described as privateers as, yet again, England was at war with France and they attacked French shipping. The ‘other side’ had their chaps of course, men such as Charles de Savoisy and Pero Nino.

An Italian, Margaritone of Brindisi, allied with Sicily’s Norman lords and became a Grand Admiral, promoting himself in 1185 to Count of Cephalonia and Zante. He was captured in 1194 while defending Naples and died in a German prison, while in 1228 the first pirate to be hanged in England was William de Briggeho.

The announcement of

The announcement ofWillam de Briggeho’s hanging in 1228

Another known pirate was a Flemish cleric, previously of the Benedictine order, Eustace the Black Monk. He fled his home town of Boulogne and fell in with pirates from the Channel Island of Jersey at some time near 1203. As long as he only plundered French shipping he was permitted to ply his pirate trade in the English Channel when granted a free rein by King John. He upset John, however, and fled to France, where he then served the French king in the same manner. He led a pirate force against the English in 1217, but was caught in a battle near Dover where the English used lime as a weapon. The French fleet was defeated and captured. Eustace was beheaded.

With the problem of pirates escalating, the Germanic cities of the Baltic formed the Hanseatic League in 1241. This was a guild of merchants who were responsible for matters maritime. By the start of the fourteenth century, this trade group had included nineteen ports and the Hanse had become a strong force to be reckoned with. Meanwhile, the English League of the Cinque Ports came into being to protect the trade ports between Dover and Hastings, although this lot did not have the same moralistic code as the Hanseatic League, for they vigilantly protected their own English shipping – but happily plundered everything else.

The French, English and Nordic countries were not the only ones to suffer from piracy, the Mediterranean had its share of trouble. Byzantium used pirates during various Holy Wars, and in the 1260s they made up the force of the Emperor’s navy.

Piracy increased during the Hundred Years’ War, which lasted from about 1337 to 1453, and the Hanse found that it had its opponents. The Victual Brothers were a gang of German pirates who attacked Bergen in 1392, and almost succeeded in destroying the Hanseatic League, but they were captured in 1402 by a Hamburg fleet and hanged.

Fifteenth-century pirates also caused trouble for the Scots. King Robert III made the decision to send his second son, James, to France when he was no more than twelve years old following the murder of his elder brother. Pirates captured his ship near Great Yarmouth and sold the boy to the English king, Henry IV. The poor boy, who must have been terrified, was incarcerated in the Tower of London. His father died of grief within a few weeks. Robert’s brother became regent, and Henry ensured the young boy was cared for and educated. He was to remain a prisoner for eighteen years until a ransom was paid for his release. He became James I of Scotland in 1424.

In circa 1450 a man purchased a quantity of fish from Flanders and shipped his purchase to England. He was attacked by pirates who damaged the ship and stole the cargo. Or the earlier date of 1384 when several thousand boxes of raisins and figs, wine, corn and bales of wheat were stolen after a fierce attack upon a shipping merchant.

There was piracy in the seas around Norway, Denmark, the Friesian Coast and the Baltic where ships and towns were attacked, although much of this was when one country was at war against another. In these cases piracy – or privateering – was accepted as legal spoils of war.

Piracy continued into the Tudor age – with well-known names such as Grainne O’Malley of Ireland who met with Queen Elizabeth I at Greenwich but refused to bow or curtsey as she considered herself to be an equal, and a name everyone knows. Francis Drake, a master seaman… but was he a privateer or a pirate?

The Spanish would definitely say the latter.

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Alison Morton "From Pirate to Emperor"

Roman Trade Map

The Romans, that mighty empire which we tend to think was highly organised and even more highly efficient, had as much trouble with these seafaring knaves in the 1700s as did the British government, the Spanish, the French and the Dutch, among others. Come to that, as we still do.

Researching for this article, I came across a most interesting chap…

Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus Valerius Carausius was a military commander of the Roman Empire in the third century. He came from Belgic Gaul and as a former nautical pilot, made a name for himself in 286 AD while fighting against tribal rebels. He was promoted to command a fleet, the Classis Britannica, which patrolled the English Channel. His orders – to eliminate raiding Saxon pirates.

He adapted these orders, however, and suspicion grew that he was permitting these pirates to carry out their raids in return for a portion of the loot for himself and his men. Emperor Maximian took a dim view of this and demanded that Carausius was to be arrested and executed. Equally, our guy took a similar dim view of such an insult when he heard about it. He retaliated by declaring himself emperor in Northern Gaul and Britannia, the territories known as Imperium Britanniarum.

Full size replica of a liburna, a small galley used for raiding and patrols,

Full size replica of a liburna, a small galley used for raiding and patrols,particularly by the Roman navy, in Millingen aan de Rijn, Netherlands

Backing him were his entire northern fleet, the three legions who were in Britain, a legion from Gaul, some foreign auxiliary units, some Gaulish merchant ships and various other experienced mercenaries. There has been speculation as to how Carausius managed to gain such wide support, but to my mind the answer is quite simple. As with all pirates, of any era or location, the lure of prospective treasure and a ‘get-rich-quick’ promise, was enough to attract anyone. Or he had amassed enough treasure to pay them all well. He was a pirate. A successful one. He could afford it.

The retaliatory invasion Emperor Maximian had hoped to launch in 288 or 289 AD failed and Carausius claimed this as a military victory. Was there a sea-battle perhaps, a successful blockade in the Channel?

History later repeated itself. It is possible that King Harold II, who without doubt had an experienced English navy, may have initially defeated Duke William of Normandy at sea in the summer of 1066, and then there is the English defeat of the Spanish Armada in the reign of Elizabeth I.

Whatever the truth of it is for our chap, peace was negotiated and Carausius began to lead his little corner of the empire as a true emperor, even minting his own coinage which he used to advantage for propaganda.

Roman coins

Roman coinsHis coins were of good quality silver – which had not been used for many years – and indicated a prospect of ‘better times’. They were also marked with slogans such as Restitutor Britanniae, ‘Restorer of Britain’ and Expectate veni, ‘Come long-awaited one’. It may have been this sort of appeal which endeared Carausius to the native population who were becoming dissatisfied with Rome rule - the Romano British equivalent of Brexit?

It is thought that Carausius may have been responsible for ordering the building of the Saxon Shore forts, a line of strategic defences along the east and south coast of what is now England, in order to deter the Anglo-Saxon sea raiders.

In 293 AD, Constantine I (Chlorus) reclaimed Gaul and Carausius found himself in difficulty, although not especially threatened as to invade Britain Constantine needed a fleet – most of which was under Carausius’s control. Alas, betrayal intervened. A traitor called Allectus, who was in charge of the British treasury, decided he wanted a higher position of authority, so he murdered Carausius and took power for himself. His reign lasted only a few short years as he in turn was killed.

It is interesting that in similar circumstances, although not so grand, a few of the seventeen and eighteenth century pirates set themselves up as leaders. One was Jean le Vasseur, an engineer by trade, who in around 1640 was sent by the governor of Saint Christopher Island (now St. Kitts) to oversee the island and harbour of Tortuga in the Caribbean. Le Vasseur built a stone fortress on the relatively flat top of thirty-feet of steep rock. Defended by formidable guns and supplied by water from a natural spring it was almost impenetrable.

Le Vasseur reigned as if he were an emperor, and took a percentage of all the plunder brought into harbour by various pirates. He taxed everything else that was brought in or taken out and amassed a substantial fortune for himself. Tortuga flourished as a safe haven for pirates, but le Vasseur’s prestige was fading. Excessive power all too often corrupts. He began to rule like a tyrant and his men started to turn against him. He was murdered in 1653 by his lieutenant in retaliation for raping the man’s wife.

I can’t say I feel sorry for le Vasseur. For Carausius though? I think I would have backed him as a pirate emperor. He sounds an interesting character.

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Alison adds

The legend:

Geoffrey of Monmouth, that not terribly reliable but only source of the time, relates a legend about Carausius. In Geoffrey’s account History of the Kings of Britain (1136 AD), Carausius is a Briton of humble birth, who by his courage persuades the Roman Senate to give him command of a fleet to defend Britain from barbarian attack. Once given the fleet, however, he sails around Britain stirring up unrest and raises an army against the historical Caracalla, here a king of Britain. Carausius defeats Bassianus by persuading Bassianus’ Pictish allies to desert him in exchange for grants of land in Scotland and sets himself up as king. Hearing of Carausius’s treachery, the Romans send Allectus to Britain with three legions. Allectus defeats Carausius, kills him, and sets himself up as king in his place.

The historical record:

The historical Caracalla’s full name was Lucius Septimius Bassianus and he and his brother, Geta, ended the campaign in Caledonia when their father Septimius Severus died in York in 211 AD. They concluded a peace with the Caledonians that returned the border of Roman Britain to the line demarcated by Hadrian’s Wall.

Annie Whitehead "The Vikings: Raiders or Pirates?"

To the Anglo-Saxons they were ‘the Danes.’ For the Franks, ‘Northmen’; to the Irish, just ‘foreigners.’ The Slavs knew them as ‘Rus,’ from which we get ‘Russian,’ and the Spanish kept it simple: they were ‘The Heathens.’ Between themselves the ‘Vikings’ were named for the area they came from. What they were not called by their contemporaries was ‘Vikings.’ That term came to be used somewhat later in history.

The word ‘i-viking’ means something like ‘to go raiding’, and basically that is what these skilled seamen from the Scandinavian countries were, expert seamen and part-time raiders. Unlike the Johnny Depp/Jack Sparrow type Pirates of the Caribbean of the early 1700s, the Vikings did not roam the seas in deliberate search of merchant ships, or heavily-laden Spanish treasure ships to prey upon. Nor were the Vikings like the eighteenth century pirates who were deserters and ne-er-do-wells. The Vikings were skilled warriors and even more skilled sailors, with a superb knowledge of seamanship and navigation.

They came from Norway, Sweden and Denmark and were a massive nuisance for England for three centuries from about the mid-700s. They were known and feared in many other countries as well, but I’m sticking to England for this article. They were finally ‘tamed’, as far as England was concerned, because of the Norman Conquest by Duke William of Normandy when he won at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Incidentally, ‘Norman’ derives from 'North Man’, the Normans were, in fact, descendants of Viking raiders.

Viking Longship

Viking LongshipIn 1002, King Æthelred II (the Unready) took Emma, the daughter of Duke Richard I of Normandy, as his wife. His intention was to seal a treaty to ensure that Normandy would cease allowing Vikings to overwinter along the Normandy coast from where they preyed on England. The idea did not work. Æthelred ended up paying the Danes more and more money to ‘go away’ and eventually one Danish King, Cnut, ended up as King of England… married to Æthelred’s widow. Her son by Æthelred, in turn, became King of England in 1052. His name was Edward – later known as the Confessor.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle makes much of one of the first (recorded) raids on the English coast by Vikings when it mentions: "on the Ides of June the harrying heathen destroyed God’s church on Lindisfarne by rapine and slaughter." This was in 793, with Lindisfarne one of the holiest places outside of Rome. The attack was witnessed by a monk, Simon of Durham: "(they)… laid everything waste with grievous plundering, trampled the holy places with polluted feet, dug up the altars and seized all the treasures of the holy church. They killed some of the brothers; some they took away with them in fetters; many they drove out, naked and loaded with insults; and some they drowned in the sea."

Whether using the term ‘raiding’ or ‘piracy’, the Vikings never intentionally aimed at desecrating the Christian God. Religion had nothing to do with it. A stockpile of gold and riches, virtually undefended, was the sole lure.

In 795, Iona, an island off the west coast of Scotland, was raided, then again in 802 and 806, the latter of which saw sixty-eight monks and laymen slaughtered. Ireland, Wales and the other islands of Scotland were also frequently raided. One of the Norse raiders who plundered the Hebrides was Svein Asleifarson. After his raiding on the islands, he sailed to Dublin, capturing two merchant ships en-route and relieving them of their cargo – fine quality broadcloth. Ah, now that was piracy!

Those early raids soon expanded into actual settlement when the Norse started to establish suitable bases for overwintering; places like York, Dublin, Normandy and Novgorod. Their ships – the Longships – were well-built powerful craft with a low, sleek appearance that could glide through the sea or along shallow rivers. They could be easily beached and were light enough to be carried overland if necessary. A rudder was on the steerboard side (which later became ‘starboard’) and had a single mast and sail. No wind? The crew rowed.

To the astonishment of some experimental archaeologists who had recreated a full-size longship, during trials they discovered that these ships were capable of being very fast. In fact the accompanying in-shore motor-powered lifeboat had to radio them to slow down – it couldn’t keep up.

It was also discovered that in the right conditions and if enough speed was reached the longboat would aquaplane for several yards: row, row, row, skim…, row, row, row, skim… I think the word formidable fits in here rather nicely!

But were the Vikings opportunistic raiders, or were they ruffian pirates? I’ll leave you to decide.

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Tony Riches "An Interview With Helen Hollick"

Hello everyone! First of all, thank you Tony for inviting me as a guest on to your blog: I’ve had a look around and you have some very interesting articles here. I’ll try to match the standard!

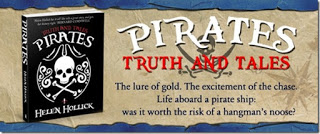

I’m here to talk about my latest release, a non-fiction light-hearted read: Pirates: Truth and Tales which is due for publication in in paperback by Amberley Press in July 2018 and a little later in the year in the US – but already available for pre-order, I believe.

I usually write fiction, some ‘straight’ historical fiction – the 1066 era and a trilogy about King Arthur, and a nautical adventure series about – well, pirates. One pirate in particular, a made-up scoundrel of a loveable rogue who gets into all sorts of swashbuckling scrapes – and manages, somehow, to get out of them again. My tag line is: ‘Trouble follows Captain Jesamiah Acorne like a ship’s wake.’

The love of his life is Tiola, a healer, midwife and white witch, but he is often torn between loyalty to her and the pull of the sea and his ship, Sea Witch. I wrote the first in the series - titled Sea Witch - because I enjoyed the fun of the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie and wanted to read something similar. I couldn’t find what I wanted for adults, so wrote my own. I am currently writing the sixth Voyage, Gallows Wake.

Amberley Press, however, approached me to write a non-fiction book about pirates to explore the truth and the tales of these dastardly rogues. Why is it that we adore tales of pirates, dress up like them, have pirate festivals and fun days, when in reality they were the terrorists of their age, the early eighteenth century? Although this ‘Golden Age of Piracy’ only lasted a few short years, those years almost brought the cross-Atlantic trade to its knees.

I was a little hesitant about producing a non-fiction book, having never really written one before. I did produce a ‘tips on writing a novel’ booklet, but I don’t count that. Then I figured I had posted quite a few interesting (I hope!) articles on my own blog and as guest posts for other blogs, so why not give it a go? My aim was to be light-hearted, maybe a little tongue-in-cheek and to explore this nautical world of cutlasses, treasure and high-seas Chases with a touch of fun, interspersed with the serious side of pirates. Many of them, despite our romantic view, were not very nice people. To break up the factual sections in the book I also delved into the fiction that we enjoy, including excerpts from some popular fiction. Fingers crossed.

What is your preferred writing routine?

I wish I could say I have one, but I don’t. I try to do the ‘admin’ type work of a morning: Facebook, Twitter, answering emails, and I run an historical novel review site called Discovering Diamonds which primarily supports indie/self-published writers but we also review traditional mainstream and the occasional non-fiction book.

I try to write of an afternoon – if the dogs don’t need walking, the garden doesn’t need weeding, the horses don’t need attending to. I live in an eighteenth century Devonshire farmhouse surrounded by thirteen acres of land, with my study windows overlooking the beautiful Taw Valley. It’s no wonder I get distracted!

What advice do you have for new writers?

Get professionals to edit your work and design your covers. Yes I know it costs money, but you have put a huge amount of effort into getting your book written, doesn’t that effort deserve the best quality when it comes to the final production stage?

What have you found to be the best way to raise awareness of your books?

Marketing can be time-consuming, but marketing is essential. Having a fabulous on-line ’shop window’ website, blog, Facebook or Twitter page etc., and encouraging potential readers to ‘come inside and browse’ often seems a hopeless task, but the trick is to be interesting and varied, and don’t keep on and on about your books. I generate most interest through my blog Let Us Talk of Many Things and I think I draw in the visitors because I vary my own posts and also host guests. Whether anyone actually reads any of it is another matter, *laugh*.

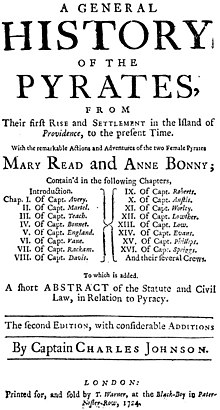

Tell us something unexpected you discovered during your research

One of the chapters in Pirates: Truth and Tales relates to the book A General History of the Pyrates by Captain Charles Johnson. It was written circa 1724 and the thing is, we don't know who Charles Johnson actually was; the name is a pseudonym. Usually, the author is assumed to be Daniel Defoe but while researching this section I came to realise that Defoe knew nothing at all about seamanship or pirates, so why would he write this book? And I came up with a very logical, and I’m convinced, correct, conclusion. Except I’m not divulging it here. You’ll have to read the book.

What was the hardest scene you remember writing?

The final scene in my Arthurian Pendragon’s Banner Trilogy. Set in post-Roman era the trilogy is based on the earlier Welsh legends, not the Medieval tales, so there are no knights, no holy grail, no Lancelot, no Merlin, just the story of the boy who became the man, who became the king, who became the legend. Except we all know what happened to Arthur in the end. He dies. And writing his death, after being with that character for something like ten years, was very hard to do.

What are you planning to write next?

More of Jesamiah - and I have recently completed a non-fiction book about smugglers which is due to be published in early 2019. I’m quite excited about it!

Thank you again, Tony, for being one of the hosts on my Virtual Book Tour. I have enjoyed my visit to your blog.

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Lucienne Boyce "Anne and Mary: Pirates! "

Women were regarded as possessions. One in four died in childbirth and most women were ignored by those who wrote the history of the time, because the writers were all men. Those women who were mentioned were associated with men as a wife, mother or daughter, or because of their charitable works. A few, however, did defy the law and society and became notorious for their daring. Mention pirates to anyone and the names Anne Bonny and Mary Read usually pop up. Both were the real pirates of the Caribbean.

Anne Bonny

Anne Bonny Anne was the lover of Calico Jack Rackham, and Mary a member of his crew. We know about them because they were caught, tried and sentenced to hang. Some of what we know, however, is romantic fiction intertwined with the facts.

For a start, the spelling of their names is uncertain: Anne or Ann? Bonny or Bonney? Read or Reed? They are usually thought of as being disguised as men, but it does seem that once aboard Rackham’s ship they did not pass themselves off as male. Yes, they wore male apparel, but skirts, corsets and such do not combine well with climbing rigging, hauling in anchors – or boarding a victim after a successful Chase.

Mary Read

Mary Read Mary was the illegitimate daughter of a sea captain’s widow. Born in England in the late 1600s, she disguised herself as a man when she served in the army fighting in battles, proving herself as capable, and only revealing herself when she fell in love and married a Flemish soldier.They purchased a tavern, the Three Horseshoes near Breda in the Netherlands, but her husband died not long afterwards and Mary returned to the army, again in male uniform.

When peace came, she joined a ship’s crew – still as a man – bound for the Caribbean. The ship was captured by pirates and she joined them, whether she maintained her disguise we do not know. At Nassau in 1718 or 1719 she took the King’s Pardon of amnesty but met with Anne Bonny and Jack Rackham and returned to piracy. Were Anne and Jack initially aware of her gender I wonder?

Anne, on the other hand, was the daughter of a lawyer, William Cormac, although when she was a child he was not fortunate financially. She was born to a serving woman around 1700 in Ireland. The family emigrated to Charlestown South Carolina when she was about twelve. Anne’s mother died soon after and her father re-establishing himself in a profitable mercantile business.

According to legend, Anne had red hair, a fiery temper and was ‘a good catch’. Did this mean she was attractive or referred to her father’s growing fortune? Against her father’s wishes she married a sailor, James Bonny, who probably had hope of doing well by his father-in-law’s estate. He was to be disappointed, as Cormac disowned both of them and they fled to Nassau.

James spent most of his time in the taverns employed surreptitiously by Governor Woodes Rogers to keep an informer’s eye on any pirate who broke the agreement of amnesty. It seems that Anne, disillusioned by her lazy drunk of a husband, grew bored.

She met the dashing ‘Calico’ Jack Rackham and became his lover. Her husband had her arrested for adultery – the punishment for which would be a public flogging for Anne – but James Bonny dropped the charge and sold her to Jack. Rackham stole a ship, renamed her Revenge and returned to piracy, taking Anne with him.

They were to be mediocre pirates, moderately successful but nothing spectacular. Anne and Mary’s gender was, after a few captured Prizes, soon widely known with their fighting ability reported as competent and efficient with weaponry, although Anne was said to be somewhat vicious and ruthless. They ended their days of piracy when their ship was captured one night, while at anchor, by a pirate hunter. Rackham and his crew were below, dead drunk. Bonny and Read fought like demons to keep their freedom, but they were overwhelmed and all were taken to Jamaica for trial.

Rackham and the men hanged, Anne and Mary had a stay of execution as they were both pregnant. Mary, alas, died of fever, but what of Anne? There is no record of her death, and it is likely that her father bought, or bribed, her freedom. But where she went and what she did after that is anyone’s guess.

One thing I would very much like to know; were Anne and Mary friends, as is usually surmised, or did they have little to do with each other? They were of a different social class, and of a different status aboard ship. Anne was the captain’s ‘wife’, Mary was crew.

Maybe the popular idea of their friendship because they were women is completely wrong? They could have disliked each other!

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Laura Pilli "Why Pirates?"

Let’s face it, the real men (and women) of the early 1700s so-called ’Golden Age of Piracy’ were not nice people. Leaving aside that they must have stunk to high-heaven, were full of fleas and lice and probably had unpleasant sexually transmitted diseases, most of them would as soon cut your throat as look at you.

Those of us who enjoy reading pirate-based novels, watching swashbuckling movies or dressing up in pirate costume to attend a party or one of the pirate festivals that happen in the UK and US, tend to turn a blind eye - complete with pirate-patch - to the gruesome reality.

I blame Johnny Depp, or more accurately, Jack Sparrow. Apologies. Captain Jack Sparrow. Between them they resurrected the interest in pirates that had first been set in motion during the great days of Hollywood, when actors such as Errol Flynn cut a dash with his cutlass across the Silver Screen. The Disney Pirates of the Caribbean franchise let the genie (pirate?) out of the bottle again, and no one has re-stoppered it since. (I only include the first movie, The Curse of the Black Pearl, the others varied from not very good to downright terrible.)

We do not want reality, we get enough of that in our everyday lives. We want our heroes rugged and ‘fresh from the fight’, as the song lyric goes. We enjoy these adventures because they are not real. It is the danger the hero must face, the within-an-inch-of-his-life death-defying scenes. The ability to keep on fighting / running / bedroom antics even though shot / wounded / kicked in a vulnerable place where real men would be curled up on the floor clutching their nether regions howling in agony.

You know these heroes are going to get out of trouble; the thrill, the excitement, is not knowing how they do so. It is the journey that intrigues, not the destination. Pirates doing piratical things is exciting. We want them to succeed against all odds, although they have to go to hell and back first. Our heroes have to be tough, maybe a bit mean, but they must also be loyal and dependable.

As for the inclusion of fantasy, the suspense of belief is a part of the entertaining escapism. What I found frustrating after I had watched POC#1 for the umpteenth time, was not being able to find an adult novel to match the fun. There were plenty of ‘straight’ nautical adventures – by Patrick O’Brian, C.S.Forrester and such. Several very good Young Adult adventures included fantasy, but YA tends to be subtle (or entirely lacking) on the ‘adult’ content.

I wanted a hero to die for, a handsome rogue of a pirate. I wanted a believable element of fantasy for his girlfriend and I wanted the ship itself to be as much of a character as the crew, but I couldn’t find the novel I wanted to read. So I wrote my own. Sea Witch.

Trouble follows Jesamiah Acorne like a ship’s wake. He is a pirate, a scoundrel and a charmer of a rogue. Tiola Oldstagh is a healer, a midwife and a white witch. Will she capture his heart - or will the call of the sea drown their love? Will he get his girl, or will the hangman get him first?

I originally intended Sea Witch to be a one-off single novel but I am currently writing the sixth in the series, Gallows Wake – the seventh if you include a short ‘prequel’ novella, When The Mermaid Sings.

You see, my hero, Jesamiah, strode into my life several years ago and stole my heart. He still hasn’t returned it, nor is he likely to, but then he's a pirate and that’s what pirates do isn’t it? Steal things!

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Mary Tod "That Essential Element… for a Pirate"

No. He needs a ship. Without a ship a pirate wouldn’t be a pirate, he’d just be a thief – unless he had a horse, in which case he would be a highwayman.

Most pirates stole their ships, upgrading to something bigger and faster, or something a little more sea-worthy than their current one. They also did not appear to have much imagination when it came to re-naming their stolen prize as there were quite a few vessels named Ranger, Rover or Revenge. But when writing fiction we have the freedom to be a little more inventive. I named pirate’s ship Sea Witch because the lead female, Tiola, is a midwife, healer – and white witch.

I came up with the idea for an adult pirate adventure soon after thoroughly enjoying the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie, The Curse of the Black Pearl. It was enormous escapism fun. I wanted something similar to read, but couldn’t find anything: plenty of young adult, plenty of ‘straight’ nautical fiction, nothing with a charmer of a hero and a touch of fantasy written specifically for adults though. So I wrote my own. I had intended it to be a ‘one off’… I am currently writing the sixth voyage in the series, seventh if you count an e-book-only novella prequel, When the Mermaid Sings.

Sea Witch

Sea Witch However, writing an adventure/fantasy yarn with strong characters and exciting situations for them to fall into and get out of relatively unscathed was one thing, creating the whole novel with that essential sense of reality, quite another. I did use ‘poetic licence’ with some historical dates here and there, but because I also included a touch of fantasy I needed to ensure the believability throughout. I did this by writing the nautical details as accurately as I could, thus blending fact (hopefully seamlessly) with fiction.

Problem. I have never been aboard a moving tall ship (the Cutty Sark and HMS Victory do not count!) Writers are so often advised ‘write what you know about.’ Which can be somewhat limiting, especially if you write historical fiction. Ah, but that is where the magic comes in: the skill of being able to travel through the mind to the world of Imagination where anything is possible. Although a hefty chunk of serious research helps.

I read all I could about anything that involved sailing tall ships: non-fiction and fiction. I soon discovered that there are limits to using certain phrases such as ‘clew up there’, ‘ship ahoy’ and ‘weigh anchor’, so the imagination came into play for putting these phrases into different contexts and situations. Interestingly, I rarely came across ‘splice the mainbrace’ or ‘shiver m’timbers!’

To get the right feel of a ship, the sounds, the movement, the hard work involved (maybe fortunately, not the smells!) you cannot do better than watch that excellent movie Master and Commander. A brilliant movie about life at sea.

The craft of creating a good, enjoyable novel is to immerse your readers in the tale from the very first opening sentence, and then carry them on through a journey of wondrous adventure – be it in a novel of historical content, a contemporary romance, science-fiction, a mystery or thriller or whatever genre you prefer to write. It can be an amusing tale, a romantic one, a scary one, sad, nail-biting, thought-provoking – but every novel must be a doorway that opens into another world.

Transporting a reader into that imagined place through creating a sense of believability is a wonderfully exciting thing to be able to do. And we, as authors, should thank the Muse every day for gifting us the ability to bring pleasure to our readers. And for helping us to bring such inspiring characters to life.

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Pauline Barclay "Writing Non-fiction. How Hard Can It Be?"

For one thing, when writing fiction you can make a lot of it up. Yes, you have to get the facts right. The right dates for historical fiction, the right technical knowledge for science-fiction, the right detail even for contemporary fiction. I mean, if you were writing a novel set in the USA in 2018 – let’s say a thriller, where there is a plan to assassinate the President – you would not have him travelling along to a major conference in a battered old Only Fools and Horses-type bright-yellow three-wheeler would you?

I was approached by Amberley Press to write a book about Pirates in Truth and Tales. That was basically the brief, which was fine as it seemed a fairly broad spectrum to explore. Naturally, as a fiction author I took it exactly as was written on the cover. Pirates as they were in truth, and as they are in tales. I wanted to explore why so many of us are fascinated by these cutthroat men – and women – of the past.

They were not nice people: They were thieves, murderers, rapists, kidnappers, torturers and the terrorists of their time. I’m talking the early 18th century, but those labels apply to any pirate of any age, even those of today who haunt the seas off the coast of places like Somalia. What we the readers like is the escapism fantasy created by Hollywood and novels. The Johnny Depp / Errol Flynn type of pirate and the loveable rogues of our childhood - Captain Pugwash, Captain Hook, Long John Silver… my own Jesamiah Acorne.

My plan was to produce chapters of fact about well-known pirates - men like Blackbeard, Charles Vane, Sam Bellamy, Stede Bonnet et al - blend in a few not-so-well-knowns and include some interesting facts about life at sea; what did they do in their spare time when they weren’t being pirates, what were their superstitions, what did they eat and drink? (And no, pirates did not only drink rum!)

In between these chapters I wanted to introduce some fictional excerpts to complement the preceding section. So we have the scene where my character, Captain Acorne, meets with Edward Teach - old Blackbeard himself. This was in the third Voyage, Bring It Close.

Another excerpt was by Swedish author Anna Belfrage, who included the subject of Indentured Service - or more correctly slavery - into one of the books of her time-slip Graham Saga. I included Frenchman’s Creek, the Pirates of the Caribbean Disney Franchise and Starz TV series Black Sails which was based around events before the opening chapter of Treasure Island, although this version was strictly for adult viewing.

The factual research required was hard work, but absorbing and highly interesting. The fictional additions were fun. I was pleased with the result, despite the typo bloopers which crept into the final published hardback version. Most or all of these have been corrected for the paperback version which is on sale in the UK now, and the US very soon.

Hopefully you will sail over to Amazon to plunder a copy for yourself – and enjoy dipping in and out of the different chapters at moments when you can put your feet up with a glass of wine and a chance to voyage off across the sea with some swashbuckling pirates.

Maybe you will even be tempted to increase your treasure trove by purchasing some of the novels I mention. If you do, thank you!

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Nicola Smith "Pirates: The Tales Mixed With The Truth"

When I was approached by Amberley Press to write a non-fiction book about pirates I was not sure whether to accept the commission or beat a hasty retreat towards the horizon.

Apart from one small notebook-type tips for novice indie writers - which I had written with my editor, primarily because we were being inundated by authors seeking advice and were tired of sending the same email out - the World of Fact was outside the remit of this long-in-the-tooth fiction author.

‘But hang on,’ I said to myself, ‘look at the research you have done in the past for your historical fiction.’ I had spent an entire year researching the factual detail for my novel of the events that led to the Battle of Hastings in 1066, Harold The King (titled I Am The Chosen King in the US). And what about all those research notes for the Sea Witch Voyages?

That first adventure in my nautical series sprang from the interest I had taken in reading several non-fiction books about pirates. That inner voice made sense. (Maybe it was my pirate character whispering to me? I wouldn’t put such persuasive arm-twisting past him!) And it was true, I had already undertaken a lot of research into all things piratical. I was certainly no expert, but enthusiastic interest goes a long way towards being at least a little knowledgeable.

Johnny Depp is to blame. OK, more accurately, Captain Jack Sparrow must take the responsibility for my passion. I loved that first movie of the Disney franchise, Pirates of the Caribbean – The Curse of the Black Pearl. (Must add: I didn’t think much of the others.) Yes, P.O.C. #1 was pure fantasy, completely nuts, had a very basic, well-used plot, was littered with continuity bloopers and was very much a ‘Hollywood’ movie into the bargain. But goodness, wasn’t it great fun!

I took those non-fiction pirate books with me to read while on holiday on the Dorset Coast, and as I read and made copious notes, fiction scenes surged into my mind. Again and again the thought, ‘This would make a good scene’ plunged into my imagination. Alongside those ideas the characters tumbled in as well: amiable Frenchman, Claude de la Rue, First Mate. Captain’s self-appointed steward, the curmudgeonly grump, Finch. Phillipe Mereno, a bully of a half-brother. Stephan van Overstratten, a rich Dutch merchant living in Cape Town who has a fancy for the female lead; young and pretty Tiola Oldstagh, midwife, healer and White Witch of the Old Ones of Craft.

She is looking for the stars to align, to meet up after lifetimes of waiting with her soul mate… my pirate captain. She sees him for the first time in person when he and his crew attempt to attack the Dutch East Indiaman that she is aboard. It is to be a while before they meet again. Treasure. Pirates. Rivalry. Romance. Smell the sea, feel the wind, hear the ship creaking… Will he get his girl, or will the hangman get him first?

Problem. I had not yet ‘met’ him. One simply cannot write a swashbuckling nautical tale of high sea adventure based around real events of the early 1700s, without a charming rogue of a hero, can one?

I spent the last day of my holiday strolling on a rain-drizzled beach planning out every chapter of what would become Sea Witch. I sat on a rock to think. Looked up, and there he was, standing a few yards away in full pirate regalia. He touched his hat in salute and I saw a gold acorn-shaped earring dangling from his earlobe.

‘Hello Jesamiah Acorne,’ I said.

He grinned at me, then vanished back to wherever he had come from.

So that, dear reader, is how my pirate captain introduced himself. I was confident enough to write a non-fiction book that include chapters about favourite tales in fiction and movies alongside the nitty-gritty of the truth about pirates. After all, I have the advantage of ‘knowing’ my very own pirate.

What do you mean Jesamiah isn’t real? Of course he is! Aren’t all fictional characters real to their creators and readers?

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Christoph Fischer "In The Shadow Of The Gallows"

Not via the illusive map with ‘X marks the spot’, however, as very few pirates buried their ill-gotten-gains on deserted islands. Most of the profit from what they plundered from their unfortunate sea-going victims was frittered away in the brothels and taverns of Tortuga, Port Royal and Nassau - the most popular harbours to drop anchor.

At least until the hangman came along.

Not all pirates were successful, a few were downright inept, a couple retired with an amassed fortune, although even they had their hopes of a quiet life ashore as a Gentleman thwarted. Henry Morgan among them - yes, he of the Rum Label fame. Morgan was, in theory, a privateer – which meant he had a government-granted license to plunder the Spanish, or whomever England happened to be at war with, so basically, the Spanish!

Eventually, Morgan was made Governor of Jamaica and he raked in a nice little earner from taxing the goods the pirates brought in to sell. There was so much wealth in Port Royal – known for a time as the ‘wickedest place in the world’ – that even the humblest servant could afford to buy trinkets and luxuries.

Morgan fell out of favour with the government though, and ended his days as a ‘has been’, although many mourners who remembered those bygone better days lined the route of his funeral procession. Several years later an earthquake struck Jamaica and an entire section of the town sank beneath the sea, Morgan’s grave along with it.

Pirate

PirateCaptain William Kidd claimed he had been commissioned as a privateer, originally as a pirate hunter, although evidence against him showed otherwise and he was hanged at Wapping on the River Thames. The evidence seems circumstantial and was probably brought about because Kidd failed to bring home a fortune for his sponsors.

The crew of a ship known as Bachelor’s Delight amassed a good bit of wealth between them, but again their claim of being privateers was challenged and the wealth was confiscated by King William and Queen Mary. They put it towards building a college in Williamsburg, Virginia. Although not the original building, the William and Mary College is still there today – founded on pirate loot.

Several of the famous pirates we know of hanged: Charles Vane, ‘Calico’ Jack Rackham and his crew – although not the two women who sailed with him. Anne Bonney and Mary Read had their execution delayed because they were pregnant. Mary died in gaol, but we don’t know what happened to Anne. Stede Bonnet hanged, as did the captured crew who sailed with Edward Teach – Blackbeard.

Teach himself died in a ferocious battle with the Royal Navy. After the fight, his corpse was found to have several gunshot and cutlass wounds. The body was decapitated then flung overboard, with the head displayed aboard as a trophy. He is said to haunt the area of the Ocracoke where he died. Apparently, his ghost is looking for its head.

Hanging, back then in the eighteenth century, was regarded as a family day out, a festival day where traders could guarantee good sales from the people who came to gawp at the victim; man or woman, pirate, thief, murderer, or alas a poor soul caught for ‘indecency’. Homosexual men were hanged along with the criminals, their sexuality regarded as a crime.

The one to be hanged was expected to put on a good ‘show’. Any quivering cowards were booed and pelted with detritus, those who had an air of swaggering bravado were cheered and heartily applauded.

Hanging was not a pleasant way to die; until the ‘long drop and short stop’ was introduced it could take anything up to twenty minutes to slowly strangle to death, a process quickened if family or friends hanged on to the victim’s legs and torso. And yes, that is where the term ‘hangers on’ comes from.

What the condemned wore was also important. Many a pirate headed for the gallows dressed in style and finery, with French lace at cuff and throat, plumed hat and colourful ribbons braided into the hair. The better quality these clothes and trinkets, the better advantage for the executioner, for he would later sell them for a handsome profit.

One woman, Hannah Dagoe, arrested for stealing in 1763, cheated the hangman out of his extra money by stripping off her clothes as she was taken to the gallows, tossing bits of finery to the admiring crowd and arriving at the place of execution with very little on. She then further insulted the hangman by kneeing him in the groin as he put the noose in place and jumped out of the cart, breaking her own neck.

The rope itself, after it had done its job, would be cut into short lengths and sold as souvenirs by the hangman, who was more often than not a criminal himself, reprieved with the condition that he executed others. For this reason it is very rare to have the hangman’s name or identity recorded.

The sixth Sea Witch Voyage of my nautical adventure series (or the seventh if you count a prequel e-format novella, When The Mermaid Sings) featuring ex-pirate Captain Jesamiah Acorne is in process of being written. It is entitled Gallows Wake, publication intended by early 2019. But which character is to face the threat of the noose, I am not revealing…

Trouble follows pirate captain Jesamiah Acorne like a ship’s wake. Can a white witch tame him, or will the sea or the noose claim him first?

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Debdatta "What Is It About Pirates?"

Hollywood, TV drama and novels are to blame, especially after the recent upsurge of interest when the first Disney franchise of The Pirates Of The Caribbean hit our screens with that scallywag scoundrel Jack Sparrow, portrayed by actor Johnny Depp. Even the baddies in that movie were likeable, loveable chaps! But that was the point of the movie, The Curse Of The Black Pearl, it was intended as family entertainment fun.

My own series of nautical adventures, the Sea Witch Voyages, follow the same theme, tongue-in-cheek sailor’s yarns, although written for adults, as they do include a darker, adult side with adult content. Again, intentional.

As one Amazon reviewer (nicely) put it: “The story itself [Sea Witch] was surprisingly original. A work like this is always going to draw the inevitable comparisons with Jack Sparrow’s big screen adventures, but this is exceedingly more down to earth and possesses far more soul and charm. The two main characters were fresh and endearing, especially Tiola and their relationship and struggles leant real weight to this exciting tale. I’m quite thrilled about having several more of their stories to explore in the future.” Words which I am delighted with, of course.

When writing Pirates: Truth and Tales I set out to balance the What Really Happened in that Golden Age, against the lighter side of fiction and on-screen drama. I blended the chapters about the reality - neatly, I hope - with excerpts from fiction and sections about our beloved fictional characters. But novels and movies depicting what is essentially a fairy-tale view are very different from that which comprised the reality.

Pirates were often driven into plundering merchant ships through poverty, necessity and opportunity. As sailors they mutinied if aboard a ship with a miserly captain, or became pirates when the choice was ‘join us or die.’

Only one of the more famous pirate captains, Edward Lowe, was known to be a criminal before he turned pirate. Several pirates were cruel, evil men - especially Lowe. Some were women. All were thieves and murderers.

Life in the 18th century was not easy for anyone except the gentry and the wealthy merchants. Poor food, dirty and cramped living conditions was the norm for the majority of people. Work was hard to find. Convicted criminals were hanged. They were the lucky ones, for few survived the depravations of gaol or transportation to the other side of the world – to the plantations of the American Colonies, for Captain James Cook was not due to ‘discover’ Australia until a good many years after the early 1700s.

At the start of the 18th century, the world was opening up. New countries and new goods were being found. Gold and other riches from the crumbled South American Empires funded the wealth of Spain and Europe, although most of it was spent on financing wars. The relatively new North American Colonies were emerging with lucrative tobacco, sugar and cotton plantations. The world’s oceans were becoming busy trade routes with ships getting bigger and faster, and the temptation to acquire ill-gotten plunder was an attractive prospect. Where there was trade, there were pirates. That is still the case today.

There was all kinds of valuable stuff for the taking. The Prize was the ultimate goal; a heavily laden East Indiaman on her way home from the East Indies, or a Spanish Galleon ploughing across the Atlantic from Mexico to Spain, her hold groaning with treasure.

Pursuit at sea could last from anything between an hour or two to several days, but the Prize had to be an easy target, one that would surrender without putting up a fight. Pirates had fast ships, guns, and bravado by the bucket-load. They made a noise, a lot of it, and a great amount of intimidation, shouting and jeering, banging anything that came to hand. The wise captain of a pursued ship gave in quickly, showed where the goods were stowed and made no resistance. Put up a fight, however, and pirates could turn nasty. Very nasty.

The Caribbean

The CaribbeanWith a hold filled with looted booty the destination for any pirate crew was the nearest town that had an adequate harbour with taverns and brothels a-plenty. Few pirates became rich for most of them spent their ill-gotten gain almost as soon as they gained it. Many pirates were riddled with sexual diseases. Nearly all were permanently drunk. A pistol shot or the hangman’s noose awaited most of them. It was a short life, but, apparently, a merry one.

I’ve written five novels in my Sea Witch series, six if you count an e-book novella (When The Mermaid Sings) with the next adventure, Gallows Wake, half completed as I write this. And I have written Pirates: Truth And Tales, a factual book with excerpts from fiction, but the question remains; Why this fascination that we have for pirates?

If ever I discover the answer, I’ll let you know.

"You know I'm bad, I'm bad - come on, you know

(Bad bad - really, really bad)

And the whole world has to

Answer right now

Just to tell you once again,

Who's bad..."

Michael Jackson’s words sum pirates up very well. The real pirates were bad.

Really, really bad.

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Discovering Diamonds "It's Been An Interesting Voyage Round The Blogs"

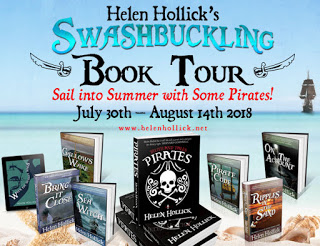

I started a sixteen-day on-line 'virtual' book tour on July 30th 2018, Voyaging Around the Blogs with the paperback release of Pirates Truth And Tales, and my Sea Witch Voyages series of nautical pirate-based adventures. With only two more harbours remaining in which to 'drop anchor', I thought I would take advantage of the #DDRevs Weekend Spot not just to do a bit of trumpet tootling, but to explore a few thoughts about Blog Hops, Tours, Chains and so on.

Are they worth the effort?

Basically, 'hops', 'tours', 'chains' are the same thing; authors post a series of articles either written by themselves or other authors/guests, on their own Blog or by 'hopping' from one Blog to another with links to the next post. It is hard work, especially for the author concerned but also for the Blog Host. Well, it's hard work if done properly.

The idea is to attract new readers for our books; Blogs, Websites, Facebook Page, Twitter Account etc, are available to us as authors. It is all very well having a presence on social media and having our books listed on Amazon, but one person - especially an indie writer - can be a mere tadpole in an ocean of millions of other authors. Only the very top writers enjoy 'whales in a pond' status, e.g. J.K.Rowling, George R. Martin…, and have no need to tout their wares. The rest of us do.

Ideally, to make a Blog Tour or one of its variations a success, the host needs to market/advertise as well - and not just 'their' day of hosting an article, review or whatever, but the other ports of call as well - in other words networking, one link linking to the the next which links to the next and so on. In practice, this rarely happens because individual authors are too busy promoting their own books, understandably, and keeping themselves afloat and in the public eye. Do remember, though, if you promote other authors by sharing, re-tweeting etc, they are likely to promote you in return. The opposite also applies!

I wrote sixteen different articles for my tour, all of them related in one way or another to my book Pirates Truth And Tales. Okay, a few did overlap a little.

Articles ranged from A Pirate Who Declared Himself A Roman Emperor through Were Vikings Pirates Or Raiders? to Medieval pirates, Female pirates, The Noose - the inevitable end for pirates, Why Do Readers Love Pirates and finally Governor Woodes Rogers of Nassau, The Man Who Knew About Pirates.

I enjoyed writing them, as I also enjoyed writing the book. I did have doubts about writing non-fiction when Amberley first approached me, but then I figured that I had been writing non-fiction articles for various blogs for several years, so why not take the research notes I had amassed for the background information needed for the Sea Witch Voyages and turn them into a book?

Why not take a look at the truth about pirates and add in the Hollywood version and the romantic fictional side as well? I was delighted with the result, although disappointed that the publisher managed to print the hardback edition from an uncorrected version of the files I submitted, resulting in too many typo errors. The mistake has been corrected for this new paperback edition, although, inevitably, a couple of very minor overlooked typos remain.

The errors served a huge purpose, however, by proving that us indie writers who use Print on Demand (POD) have several huge advantages over traditional mainstream writers: We take as much care as we can to ensure the edition that 'goes live' is correctly formatted and are the correct files to be published. We edit, edit, edit, edit - unlike mainstream publishers who seem to be cutting financial cost corners as much as they can. If we blunder we can very quickly re-edit and re-publish. We are in control!

But as for Book Tours... are they worth it? From a sales perspective, alas, probably not. For networking and reaching a wider audience probably yes. Note the word 'probably'.

For enjoyment and meeting new people - definitely.

Two disappointments for me; very few people leave comments beneath posts. The same applies here on Discovering Diamonds, but that may, in part, be a problem with Blogger/Google and WordPress, especially, I've noticed, now that GDPR has come into play. Comments are just not getting through… In my case I think pirates are plundering them.

I am also a little disappointed that I have not had many new subscribers to my newsletter. We are told that sending out newsletters is vitally important… but is it?

That's a different subject though - maybe one for a future weekend, here on Discovering Diamonds?

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Sarah Greenwood "Pirates: The Truth and the Tales"

The romance of fiction, TV shows and big-screen movies have influenced our perception of the Caribbean pirates of the ‘Golden Age’ of the early 1700s. We have a romantic view of a life ‘On the Account’, we think of Jack Sparrow from the Disney franchise Pirates of the Caribbean, or Captain Pugwash from the beloved children’s TV cartoon series.

Do we care that these romantic portrayals are very far from the truth about pirates? Reality has its place, but for entertainment we like handsome heroes and pretty heroines. We enjoy the breath-taking alarm of make-believe danger and engrossing adventurous romps. Pirate stories give us the (safe) excitement we crave. Pirates seek treasure – don’t we all? How many of us hope for that winning lottery ticket every week? Although we don’t commit torture and murder to get it.

Pirates were on a get-rich-quick mission and had no scruples about how they did it, as long as they had silver in their pockets to spend in the taverns and brothels. In stories, their ships are usually pristine and fast, the flag fluttering menacingly from the masthead is always a pair of crossed bones or cutlasses beneath a leering skull. Pirates wore a gold hooped earring, they drank rum, had swashbuckling fights with lethal cutlasses (which the hero in stories always won), lusted after buxom wenches and escaped the hangman at the very last minute.

But what about the real pirates?

To answer that question, and also to satisfy the passion of readers of the romantic fictional side of piracy, was my goal in producing Pirates: Truth and Tales when Amberley commissioned me to write it. I think I managed it. I wanted to write a ‘drop in at any chapter’ book. Mostly light-hearted, easy to read and with an ‘Oh, I didn’t know that’ feel. There are a lot of factual pirate books on the shelves in bookstores and on Amazon. I wanted something that might not necessarily be unique, but certainly very different.

What I came up with were factual chapters ranging from the famous pirates, such as Blackbeard, Calico Jack Rackham, Anne Bonney and Mary Read and such, with a few not-so-well-knowns all running (sailing?) alongside more general seafaring chapters of interest. What did they wear? What did they plunder, where and how did they sell it? Where did they get their ships from? What type of ships did they use?

Interspersed with all that, I investigated the fiction. The favourite novels such as Treasure Island and Frenchman’s Creek, my own Sea Witch Voyages series of nautical adventures that have a touch of fantasy about them, plus a few more excerpts from pirate novels by other authors. The fictional complementing the factual, bringing an alternative perspective for the reader to enjoy.

The result is a delightful mixture of the romantic and the reality. The swashbuckling movie and novel versions of pirates, and the not-so-nice horror of what these men - and women - were really like.

I have to admit, honest pirate, give me the made-up romance version of pirates any day!

© 2018 Helen Hollick

Antoine Vanner "The Man Who Knew About Pirates"

I say more-or-less, because piracy continues to this day. It was never totally eradicated, although towards the end of the 1700s piracy switched back to privateering during the years of war between England and France, then the America Colonies and then the Napoleonic Wars. Privateering was legal with a government-given licence to plunder the enemy. Piracy was different. Pirates attacked anything, as long as it was worthwhile and relatively easy to do.

Captain Nathaniel Roberts

Captain Nathaniel RobertsThe personification of a fashionably dressed pirate

From 1715 to 1718 the Caribbean was alive with pirates; famous names such as Blackbeard and Calico Jack Rackham, with Anne Bonney and Mary Read, Samuel Bellamy, Howell Davis, Charles Vane… and my own fictional pirate, Jesamiah Acorne! At first no one particularly worried, but then the rich merchants began to feel the pinch as trade suffered. This was the dawn of the Atlantic trade, when sugar, tobacco and a little later, cotton, had to be transported from America to Europe. Pirates were a nuisance. Something had to be done.

The something was a someone. Woodes Rogers. The Colonies all had appointed governors, but most of them were as corrupt as the pirates. Rogers was different, he was honest and determined to put an end to the scourge of the seas.